My March 23, 2021, article for Alpha Architect addressed the issue that in recent years the field of empirical finance has faced challenges from papers arguing that there is a replication crisis because the majority of studies cannot be replicated and/or their findings are the result of multiple testing of too many factors. However, the finding that factor premium returns cannot be replicated should not be interpreted to mean there is a crisis in empirical finance. In fact, the findings should have been entirely expected because institutional trading and anomaly publication are integral to the arbitrage process, which helps bring prices to a more efficient level. Such findings simply demonstrate the important role that both academic research and hedge funds (by way of their role as arbitrageurs) play in making markets more efficient. In other words, lower post-publication premiums do not mean there is a crisis; instead, they show markets are working efficiently, as expected.

The fact that research, such as the 2016 study “Does Academic Research Destroy Stock Return Predictability?” by David McLean and Jeffrey Pontiff, has found that post-publication, premiums decayed about one-third on average as institutional investors (particularly hedge funds) traded to exploit the anomalies, does not demonstrate there was a replication crisis. It did demonstrate that factor premiums might be impacted by popularity and resulting cash flows. The research has also found that factors that are behavioral-based are more easily arbitraged away. However, even behavioral-based premiums can persist due to limits to arbitrage, which prevent sophisticated investors from fully correcting mispricings. This is especially true in less liquid stocks. On the other hand, while risk-based premiums cannot be arbitraged away, they can shrink due to increased cash flows seeking to capture the premium.

Conflicting Forces on the Factor Premium Debate

Cash flows into strategies have two effects. Initially, they increase returns as valuations increase. However, the long-term effect is to lower premiums, as the higher valuations lead to lower future returns. This is true for all risk assets, not just factor strategies. Valuations matter a great deal, and the greater (smaller) the spread in valuations between the long and short side of factors, the greater (smaller) the expected premium. Thus, the publication of findings can lead to cash flows that shrink future premiums.

Wenjin Kang, K. Geert Rouwenhorst, and Ke Tang contribute to the asset pricing literature with their March 2021 paper, “Crowding and Factor Returns.” The focus of their study was on factor strategies (carry, momentum, and value) in commodities markets because they have been employed for long periods of time. The Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) produces weekly investor positions data (see Ray Micaletti discussion for more details), and they were able to separate the positions of commercial traders from noncommercial ones. They defined crowding as the “excess speculative pressure,” measured as the deviation of noncommercial (financial speculators, including hedge funds and commodity trading advisors) traders’ positions from their long-term average in commodity futures markets scaled by open interest. Their database covered 26 commodities traded on North American exchanges (CBOT, CME, and NYMEX) from January 2, 1993, to December 31, 2019.

Following is a summary of their findings:

- The standard deviation of speculative net long positions was large (around 15 percent), indicating there is substantial time-series variation in these positions, suggesting that speculators trade for reasons other than to merely accommodate commercial hedging demands.

- The time series standard deviation of crowding averaged about 12 percent across commodities.

- Commodity level crowding predicts subsequent commodity futures excess returns.

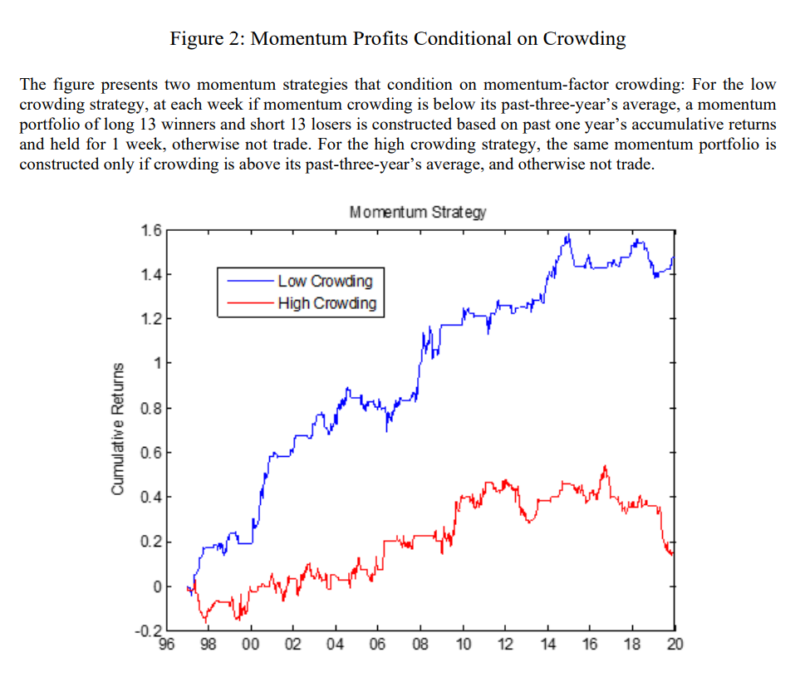

- The returns to the carry, value, and momentum strategies are highest during months when the strategy is least crowded, and lowest when it is most crowded. For example, a one-standard-deviation increase in their crowding metric decreased the return of the momentum factor by around 8 percent annualized, comparable in magnitude to the unconditional long-term average factor risk premium.

- Crowding is primarily the result of performance chasing by investors: Across all factor strategies, good past performance leads to an increase in crowding of that strategy.

- Consistent with the limits-to-arbitrage literature, the willingness of speculators to bet on factors decreases when the funding costs (proxied by the TED spread or the repo rate) are high. The willingness to bet on momentum strategies also decreases when commodity-level volatility increases (this was not true for the value and carry factors).

- The momentum factor in commodities has become more crowded since 2015 and has also experienced low average returns. However, value and carry strategies did not exhibit a similar increase in crowding or decline in their average returns.

- Their findings were robust to various alternative measures of crowding.

The above findings are entirely consistent with those from the field of behavioral finance: Recency bias results in a negative relationship between investor demand (popularity) and subsequent returns and thus is an important determinant of time variation in the returns to popular strategies, whether factor-based or not. Kang, Rouwenhorst, and Tang noted that their findings are consistent with those on equity factor strategies, citing the 2014 study “The Growth and Limits of Arbitrage: Evidence from Short Interest.” The authors, Samuel Hanson and Adi Sunderam, found that an increase in capital results in lower strategy returns. However, consistent with theories of limited arbitrage, strategy-level capital flows are influenced by past strategy returns as well as strategy return volatility, and arbitrage capital is most limited during times when strategies perform best. Consistent with the findings of McLean and Pontiff, they also noted that the growth of arbitrage capital may not completely eliminate returns to these strategies.

The bottom line is that popularity and resulting cash flows impact valuations and thus future expected returns of all investment strategies—the more you pay for the same expected future cash flow, the lower the expected return. And the publication of findings of anomalies and factor premiums can lead to increased cash flows. With that said, it isn’t necessarily the case. For example, studies such as the 2018 paper “Characteristics of Mutual Fund Portfolios: Where Are the Value Funds?” and the 2017 paper “Are Exchange-Traded Funds Harvesting Factor Premiums?” (summary here) found no evidence of crowding in equity factors for either mutual funds or ETFs. In addition, if crowding was the reason for the disappointing performance of value strategies over the period October 2016 through March 2020, how do we account for the fact that the valuation spread between value and growth stocks has dramatically widened since the publication of the famous Fama-French research on the value premium? For example, as of December 1994, the P/B ratio between value and growth stocks was 2.1. Using Vanguard’s Growth ETF (VUG) and Value ETF (VTV), at the end of February 2021 the spread had widened to 3.3, or by about 60 percent. Consistent with the findings of the two aforementioned papers, there is no evidence of crowding in the equity value factor.

Finally, it is important for investors to understand that crowding, leading to compressed spreads in valuations between the long and short side of factors, does not predict negative returns, but rather reduced premiums, in the same way that higher P/E ratios do not predict negative returns to stocks, just a reduced equity risk premium.

DISCLOSURES

Important Disclosure: The information presented here is for educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is based upon third party data which may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Third party information is deemed to be reliable but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Mentions of specific securities are for illustrative purposes only and should not be viewed as a recommendation. By clicking on any of the links above, you acknowledge that they are solely for your convenience, and do not necessarily imply any affiliations, sponsorships, endorsements or representations whatsoever by us regarding third-party websites. We are not responsible for the content, availability or privacy policies of these sites, and shall not be responsible or liable for any information, opinions, advice, products or services available on or through them. The opinions expressed by featured author are their own and may not accurately reflect those of Buckingham Strategic Wealth® or Buckingham Strategic Partners®, collectively Buckingham Wealth Partners. LSR-21-55

About the Author: Larry Swedroe

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.