Liquidity—the ability to buy and sell significant quantities of a given asset quickly, at low cost, and without a major price concession—is valuable to investors. Therefore, they demand a premium as compensation for the greater risks and costs of investing in less-liquid securities. For example, liquidity risk partly explains the equity risk premium—the average transaction costs on stock trades are larger than they are on Treasury bills, which can be traded in large blocks of tens of millions of dollars in a single transaction without affecting their price.

Academic research, including the 2015 study “The Pricing of Illiquidity as a Characteristic and as Risk,” published in the September 2015 issue of the Multinational Finance Journal, has found that the illiquidity premium in stocks is positive and highly significant worldwide after controlling for global and regional common risk factors (such as beta, size, and value). The research has also found that the market requires a higher premium for liquidity sacrifice in negative environments (for example, illiquidity increased during the great financial crisis), when investors holding illiquid equities become liquidity takers (divesting them, either to meet liquidity needs or due to panicked selling) and pay a steep price in doing so. In other words, the liquidity premium is conditional on the state of the market—it’s much smaller in good times and much larger in bad times.

The finding of a liquidity premium is consistent with economic theory, which holds that assets that perform poorly in bad times (when the marginal utility of consumption is higher) should carry large premiums. And what’s more, illiquid stocks (which tend to be smaller stocks) have greater sensitivity to liquidity shocks and thus also should carry premiums (helping to explain the size premium). Stocks whose systematic liquidity risk rises more when funding illiquidity is worse have higher expected returns. The finding of a liquidity premium also holds for corporate bonds. Corporate bond illiquidity increases monotonically when moving from safer bonds to riskier bonds, helping to explain their incremental yield.

To summarize the theory and literature on equities and liquidity, investors care about stock illiquidity and thus demand higher expected returns on stocks that are more illiquid. Variations in illiquidity affect stock valuations. Thus, investors not only prefer assets that are more liquid, but they also prefer assets that have smaller exposure to liquidity shocks. In other words, they prefer assets whose prices fall less when market illiquidity rises, assets whose illiquidity rises less when market illiquidity rises, and assets whose illiquidity rises less when there is a market-wide decline in prices.

Diminishing Illiquidity

Of particular interest is that over the past 40 years we’ve seen many technological (such as high-frequency trading) and regulatory changes (such as decimalization) that may have contributed to improving liquidity by lowering bid-offer spreads in financial markets. There may also have been impacts on liquidity caused by the dramatic expansion of the hedge fund industry, which now has more than $3 trillion in assets under management. It’s possible that hedge funds, many of which are long-horizon traders and thus incur relatively small transaction costs, might have arbitraged away (or at least reduced the size of) the liquidity premium by buying illiquid stocks and short selling liquid stocks.

Financial innovation, in the form of low-cost index funds and ETFs, may also play a role in the shrinking of the liquidity premium. Their presence allows investors to buy and sell illiquid assets indirectly lowering the sensitivity of returns to liquidity. These instruments enable investors to hold illiquid stocks indirectly while incurring low transaction costs, thereby reducing the sensitivity of returns to liquidity. For a more thorough understanding of this mechanism read my or Wes’ prior post on ETF Liquidity.

A diminishing illiquidity premium was found by Azi Ben-Rephael, Ohad Kadan, and Avi Wohl, the authors of the 2015 study “The Diminishing Liquidity Premium,” published in the April 2015 issue of the Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis. They found that the characteristic liquidity premium had significantly declined over the past four decades. It was large and robust until the mid-1980s but had become small and “second-order” since. In fact, they found that there was no longer a liquidity premium among NYSE and AMEX stocks. They also found that even for smaller stocks there was a characteristic liquidity premium in early periods, but it declined significantly and largely disappeared later, concentrated only among small stocks. Thus, to the extent that a characteristic liquidity premium currently exists in U.S. public equity, it’s economically small. They also found that the decline in the liquidity premium stems from an improvement in liquidity. This finding is consistent with markets having become more efficient following more intense arbitrage activity.

The authors noted that their results have important implications for equity valuations: “A reduction of the average annual liquidity premium from 1.8 percent to 0 percent implies a very large price effect.” All else equal, a smaller liquidity premium justifies a lower equity risk premium, providing support for higher valuations. They noted: “A 1 percent decrease in the discount rate may translate into a 10 percent-20 percent increase in valuation.” The decline in the liquidity premium may also help explain the shrinking of the small-cap premium, about which much has been written.

In terms of asset management strategies, their findings cast doubt on the liquidity-based long-short trading strategies that have become common for hedge funds. The authors did emphasize that their results were based on data from only U.S. stock markets. Our equity markets are probably the most liquid markets in the world, and it’s likely that liquidity pricing is more significant in less liquid markets.

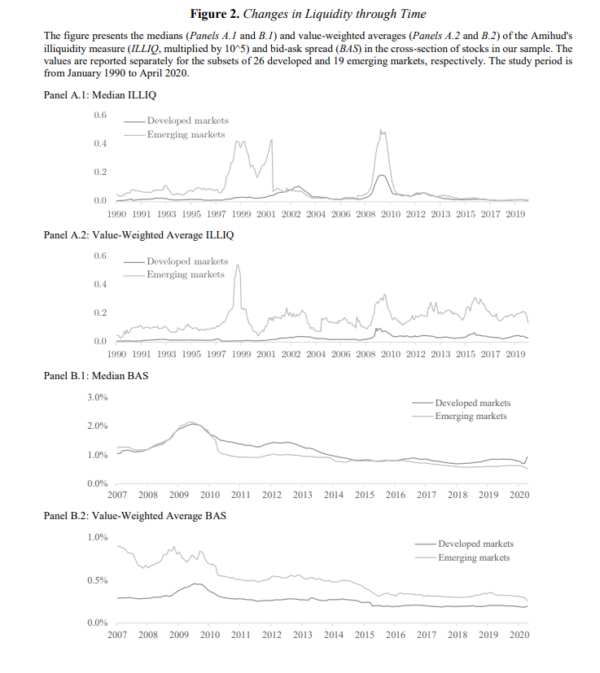

The above findings are consistent with those of the authors of the paper “The Pricing of Illiquidity as a Characteristic and as Risk,” published in the September 2015 issue of the Multinational Finance Journal, who found that there was a strong and persistent downward trend in illiquidity since the early 1970s. However, the trend had been interrupted from time to time by bear markets, during which illiquidity rises. For example, they found that while the rise in illiquidity during the 2008-2009 financial crisis was quite strong, by the close of 2014, illiquidity was lower than ever before.

This is an important finding because the sharp decline in illiquidity over the recent decades provides at least a partial explanation for the rise in equity valuations. As trading costs fall, the level of the equity risk premium should be expected to fall as well, resulting in (or justifying) rising valuations. The narrowing of bid-offer spreads and the dramatic fall in commission costs have helped improve liquidity, resulting in a smaller equity risk premium.

Latest Research

Nusret Cakici and Adam Zaremba contribute to the illiquidity literature with their March 2021 study, “Liquidity and the Cross-Section of International Stock Returns,” published in the June 2021 issue of the Journal of Banking & Finance. They performed a comprehensive investigation of the illiquidity premium in 45 international stock markets over the period 1990-2020.

Following is a summary of their findings:

- Liquidity pricing depends strongly on firm size.

- Although the premium is globally present, it exists only among microcap stocks, which have negligible economic significance—there is no evidence of an illiquidity premium among the large companies constituting the vast majority of international investable equity markets. These results hold for global, developed and emerging markets, and are robust to different methods of controlling for company size, alternative liquidity proxies and inclusion of a battery of control variables, including other equity factors.

- Within the microcap universe (which they defined as stocks with market capitalization below an inflation-adjusted value of U.S. $500 million), constituting approximately 0.2 percent of market capitalization globally, the premium is powerful and sizable—for the global markets, the least liquid stocks in the smallest firm quintile outperformed the most liquid stocks by 1.49 percent per month (t-stat = 5.75) with an associated six-factor alpha of 1.35 percent (t-stat = 5.11). The alphas were 1.44 percent (t-stat = 4.65) and 1.73 percent (t-stat = 4.29) for developed and emerging markets, respectively.

Their findings led Cakicki and Zaremba to conclude:

“Any illiquidity premium in the international stock markets is generated by the smallest quintile of companies.”

They noted that while the quintile of microcap firms may initially have appeared to constitute a meaningful and investable group (there were about 3,500 microcap firms in their sample), they only accounted for 0.2 percent of the total market capitalization of developed markets and 0.4 percent of the total capitalization of emerging markets:

“Therefore, the sizable illiquidity premium in the small firm segments can hardly be captured by any larger market investor.” They added: “If illiquidity is not rewarded anywhere except for an irrelevant segment of hardly tradeable stocks, then it should not be considered as a separate factor in qualitative portfolio management.”

These findings should leave you with two important takeaways. First, liquidity risk should be a consideration when designing your financial plan, both in terms of your asset allocation and the choice of investment vehicles. Second, the liquidity premium for taking a risk that shows up in bad times does have implications for the type of bonds used to implement the fixed-income portion of your portfolio.

The evidence presented highlights the importance of owning assets that perform well during bad times when liquidity risks show up. Thus, you should strongly consider owning only safe, liquid bonds. U.S. Treasuries are one of the safest and most liquid of bonds. As such, their diversification benefits tend to show up most strongly when needed most. While their correlation with U.S. stocks is about zero over the long term, during bear markets (when stocks are falling and their liquidity is at their worst) the correlation turns highly negative. Other safe fixed-income investments you should consider are FDIC-insured CDs and municipal bonds that are AAA/AA-rated and are also either general obligation bonds or essential service revenue bonds.

Important Disclosures

This article is for educational and informational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal or tax advice. The analysis contained in the article is based on third-party information and can become outdated or otherwise superseded at any time without notice. Third-party information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. By clicking on any of the links above, you acknowledge that they are solely for your convenience and do not necessarily imply any affiliations, sponsorships, endorsements or representations whatsoever by us regarding third-party websites. We are not responsible for the content, availability or privacy policies of these sites and shall not be responsible or liable for any information, opinions, advice, products or services available on or through them. The opinions expressed by featured authors are their own and may not accurately reflect those of Buckingham Wealth Partners, collectively Buckingham Strategic Wealth® and Buckingham Strategic Partners®. LSR 21-80

About the Author: Larry Swedroe

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.