The first ETFs emerged in 1993 and closely tracked broad-based indexes for a low fee. Since then, the competitive situation in the ETF industry today has differentiated itself by adding a new breed of ETFs that reflected specialization into popular investment themes. When the evolution of the ETF industry is compared to the evolution of mutual funds, the picture that emerges is different in two ways. First, ETFs were essentially passive products. They were never promoted on the basis of exceptional managerial skill as mutual funds were and continue to be. Second, the transparency of the ETF structure also precluded the industry’s ability to promote high return or high yield characteristics without disclosing the full scope of the risk profile of the product.

Competition for Attention in the ETF Space

- Itzhak Ben-David, Francesco Franzoni, Byungwook Kim, Rabih Moussawi

- The Review of Financial Studies

- A version of this paper can be found here (prior coverage on earlier version of paper here)

- Want to read our summaries of academic finance papers? Check out our Academic Research Insight category.

What are the research questions?

- What has been the trend in the competitive dynamics of the ETF market, to date?

What are the Academic Insights?

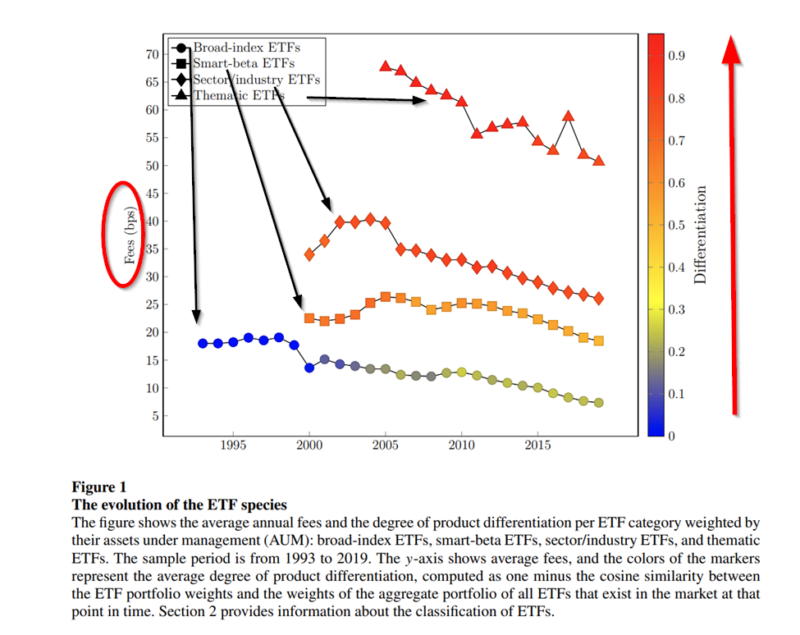

- A picture of the evolution of ETFs since 1993 is presented in Figure 1 below. The colors of the markers represent the degree of differentiation (least differentiation is blue, most differentiation is red). The sample consisted of all ETFs traded in the US equity market through December 2019. Over the period analyzed, fees declined across the board while product differentiation increased. The first products were passive ETFs designed to track broad-based indexes like the S&P500. Although fees were relatively low in the beginning, increasing competition led to even larger declines in fees over time and increasing differentiation. More specialized ETFs began in the form of smart beta and sector-based ETFs, following relatively quickly by theme-based were introduced sequentially and characterized by higher fees, and larger profits, than their low tracking error predecessors. At the end of the observation period, specialized ETFs managed 18% of the industry’s assets, yet they generated about 35% of the industry’s fees. Overall, the competitive environment has evolved towards a definite focus on differentiated products while coexisting with broad-based ETFs. The authors argue in theory, that the two segments can coexist, where broad-based ETF products compete on price and specialized ETFs compete on quality. There is a notable difference in the sensitivity of demand flows to ETFs fees and past performance for broad-based (index and smart beta) ETFs. While investors in broad-based products were quite sensitive to fees and specialized (theme and sector) ETFs were sensitive to past performance and unrelated to fees. If however, the media exposure to the stock contained in an ETF portfolio, the fee sensitivity was mitigated to some extent.

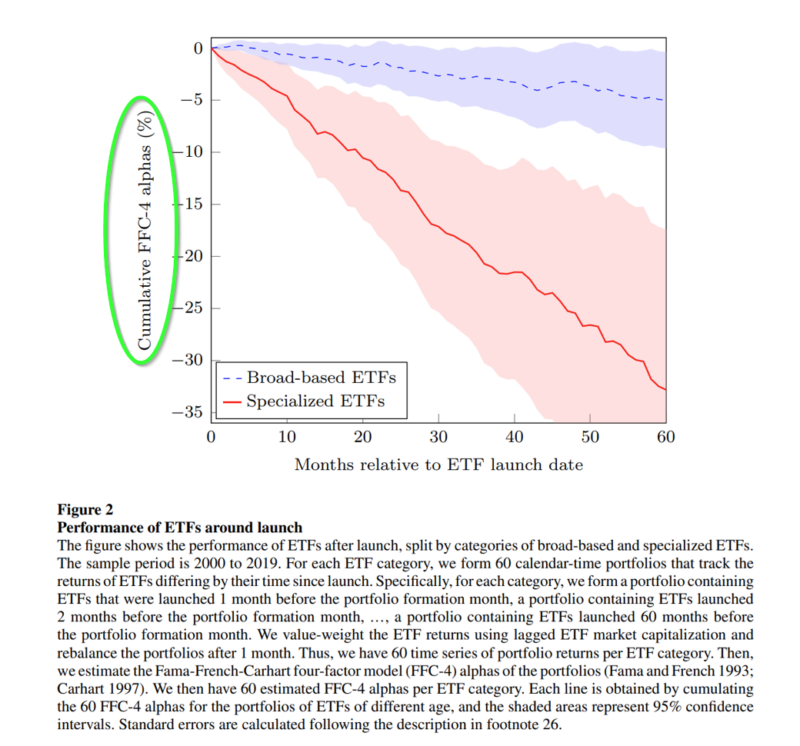

- What makes specialized ETFs appeal to investors? Performance, both raw and risk-adjusted. However, the facts do not align with those expectations. The weighted risk-adjusted return for all specialized ETFs was a disappointing -3.2% annually, after fees. See Figure 2 just below. The negative performance can be attributed to specialized ETFs most recently launched with a gross return of -6% over the post-launch 5 years. However, the underperformance is not due to higher fees or transactions costs. Some comfort can be found in the absolute size of the specialized ETF market. As of 2019, it was approximately $460 billion AUM. As a comparison broad-based ETFs were only slightly negative, although not significant.

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged and do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index.

Why does it matter?

The implications of the competitive landscape for ETFs are mixed. On one hand, they have truly democratized investing. Investors now have access to the benefits of financial markets in one instrument that provides diversification at very low fees. Recently advertised fees on broad-based bond funds have fallen to 3bps. On the other hand, ETF providers have been able to satisfy investor demand for increasingly specialized products even though the evidence suggests they underperform. Are investors becoming worse off due to the effectiveness of the marketing strategies by providers of specialized ETFs?

The most important chart from the paper

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged and do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index.

Abstract

The interplay between investors’ demand and providers’ incentives has shaped the evolution of exchange-traded funds (ETFs). While early ETFs invested in broad-based indexes and therefore offered diversification at low cost, more recent products track niche portfolios and charge high fees. Strikingly, over their first 5 years, specialized ETFs lose about 30% (risk-adjusted). This underperformance cannot be explained by high fees or hedging demand. Rather, it is driven by the overvaluation of the underlying stocks at the time of the launch. Our results are consistent with providers catering to investors’ extrapolative beliefs by

issuing specialized ETFs that track attention-grabbing themes.Received July 16, 2021; editorial decision May 28, 2022 by Editor Ralph Koijen.

I freely concede that the ETF is the greatest marketing innovation of the 21st century. But is the ETF a great innovation that serves investors? I strongly doubt it. In my experience…I have learnt to beware of investment “products,” especially when they are “new” and even more when they are “hot.”

—John Jack Bogle, Financial Times, March 15, 2015

About the Author: Tommi Johnsen, PhD

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.