Several terms can be found within the framework of ESG investing– Impact investing, Sustainable Finance, Socially Responsible Investing, Climate risk and so on, all of which may or may not refer to the same theme. Legitimately, the definitions of ESG investing and associated products should depend on the context. The author argues the current confusion within the ESG field is closely related to the mixture of “value versus values” as dual motives expressed by investors. The combination of the rapid growth in demand for ESG products and the notion that investors have varying motivations and return expectations within and across ESG categories, has resulted in a mishmash of terminology and unreliable performance results. The author of this piece dissects the “value versus values” problem.

Because of the misunderstandings about investor and managers motivations, people often talk at cross purposes about ESG. Therefore, it is incumbent upon the finance research community to provide clearer analyses and interpretations of these issues from a financial economics perspective. In particular, finance researchers have an opportunity to make important contributions to the literature and society by conducting research that considers both pecuniary and nonpecuniary aspects of ESG, taking an objective stance with regard to the incentives, costs, and benefits related to sustainable finance, and that provides evidence on the associated economic implications.

Presidential Address: Sustainable Finance and ESG Issues—Value versus Values

- Laura T. Starks, The President of the American Finance Association, 2022

- Journal of Finance

- A version of this paper can be found here

- Want to read our summaries of academic finance papers? Check out our Academic Research Insight category.

What are the research questions?

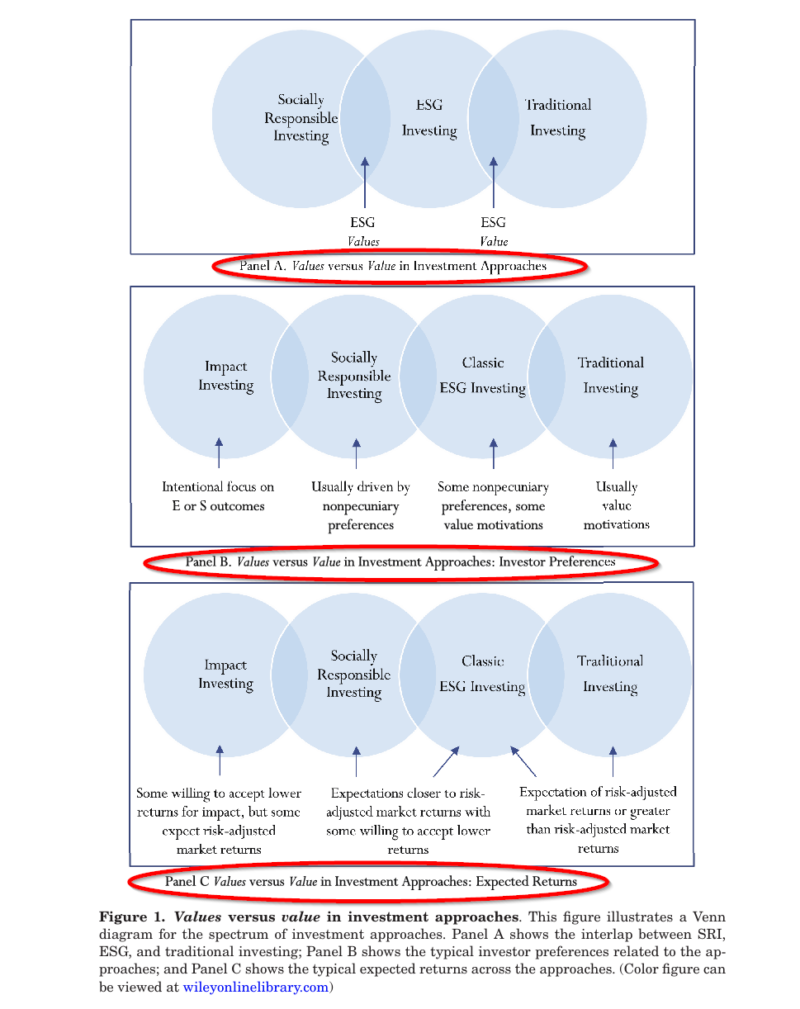

To begin the discussion, the author argues that the terminology used to define ESG is the main issue. There are no clear definitions of each term and how it differs from the others. The context matters as does the scope of the reference. It is unlikely that ESG is the best term to describe various motivations for investors, managers, institutions and corporations. There is a need for researchers to frame the question one way or another. The author suggests framing the question as a Venn diagram presented in Figure 1, across panels A to C.

- Panel A: ESG investing may matter to those focused on SRI and traditional investors. SRI investors may primarily view ESG from a values point of view. Otherwise, traditionalists who invest in ESG do so from a value point of view.

- Panel B: Add impact investors who are focused on environmental and social outcomes. SRI investors, on the other hand, want to avoid investing in firms that do not align with their own values. Classic ESG investors may also mix the value and values objective.

- Panel C: Add expected returns that span a willingness to accept lower returns for value alignment to a desire to earn risk-adjusted returns.

- Most ESG strategies and products can be subsumed by the interlocking spheres including positive screening or tilt, ESG integration, negative ESG screening, and ESG risk management

What are the Academic Insights?

- Motivations for investing in ESG products: investors, and managers.

- Motivations for ESG investing are either value-based or values-based. If an investor uses information on the ESG attributes to value a stock, then the investor is interested in enhancing the risk/return properties of the investment and may communicate with the firm’s management in an effort to influence ESG-related decisions.

- On the other hand, if the motive is nonmonetary or values-based, the decision to invest is a function of whether or not the firm is associated with products, decisions, or activities that align with acceptable ESG principles, especially with respect to the environment, societal or sustainability goals.

- Theoretical research on ESG has expanded along roughly similar lines, although empirical studies have failed to meet the challenge necessary to discern the impact of motivation on performance results. Much of the research on motivational differences has been conducted with surveys or in an experimental context. Although this research has begun to address the range of differences in ESG investor groups, more work is required. Deeper dives could include the following: 1. Are value versus values groups complementary or competitive? 2. How does that affect market prices? 3. Are the answers the same across various theoretical frameworks?

- An in-depth analysis of the motivations of managers and corporate boards are of particular interest given the serious criticisms of greenwashing leveled at corporations. It turns out that the empirical evidence on the ESG profiles of firms fails to match up to its’ activities, markets, ownership characteristics, risk profile and its’ value is contradictory. It may be that managers are simply responding to investor demand for stronger environmental brands.

2. The Value versus Values performance issue:

- Thousands of studies have been conducted and published in academic and practitioner outlets on ESG. However, the ability to conclude from the evidence that ESG adds to firm value or outperforms benchmarks with confidence is nonexistent. The conclusions are mixed or inconclusive and not surprising given the span of investment strategies that are subsumed under the ESG umbrella. Strategies have varying objectives, approaches, and may try to appeal to one or both types of ESG investors. The concoction of funds not only impairs the ability to assess performance but impedes the larger picture in terms of the environment, for example, and other social issues. Is the omission of sin stocks or pharmaceutical stocks due to religious objections equivalent to the omission of fossil fuel stocks due to concerns about climate change? Should we expect similar performance? If not, why combine this type of universe variabiilty into an empirical analysis?

- Along those same lines, empirical studies on ESG lump all sorts of funds without differentiating between investor motives and preferences. Heterogenous groups of investors with preferences towards child labor, gender, diversity, climate change and so on, should not be mixed into a sample that is ultimately compared to a benchmark and analyze the effect that the ESG portfolio has on the environment or societal issues.

Why does it matter?

The relationship between financial markets and ESG investing is obscured by the lack of clarity regarding motivations for investing in ESG strategies. Is the motive to align the investor’s values with the ESG theme? Or is the ESG term a misnomer for a set of stocks that are systematically undervalued, for some reason as a function of its ESG characteristics? For financial and economics researchers: “…….there is an incredible opportunity to meaningfully contribute to this critical topic, to society, and to public policy by delving deeper into understanding how value and values orientations and their interactions impact the relations among investors, companies, and societies.”

The most important chart from the paper

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged and do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index.

Abstract

In this address, I discuss differences across investor and manager motivations for considering sustainable finance—value versus values motivations—and how these differences contribute to misunderstandings about environmental, social, and governance investment approaches. The finance research community has the ability and responsibility to help clear up these misunderstandings through additional research,

which I suggest.

About the Author: Tommi Johnsen, PhD

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.