Behavioral finance is the study of human behavior and how it leads to investment errors, including the mispricing of assets. While a great deal of attention has been given to how investor behavior influences stocks prices—creating anomalies (such as momentum and the lottery effect—the impact of markets on the psychological health of investors has not been extensively explored. With that said, recent studies have found that there is a correlation between stock market downturns and an increase in hospital admissions for mental illness, an increase in domestic violence, deteriorating mental health among retirees, and increased depression rates.

Chang Liu and Maoyong Fan contribute to the behavioral finance literature with their February 2024 study, “Stock Market and the Psychological Health of Investors.” Utilizing a large, national, individual-level data set that includes inpatient, outpatient, and pharmaceutical data, they examined the impact of stock market fluctuations on investors’ mental health. They began by citing data that showed that about 58% of the U.S. population owned stocks and that stocks represented 41% of the total financial assets held by U.S. households. Given the large body of evidence demonstrating that investors exhibit loss aversion (a real or potential loss is perceived by individuals as psychologically or emotionally more severe than an equivalent gain), and the fear of loss can cause investors to behave irrationally and make bad decisions, their hypothesis was that bear markets would have negative effects on investor psychological health. Further, since stock fluctuations can influence investor behavior, they could create positive or negative feedback loops that influence prices.

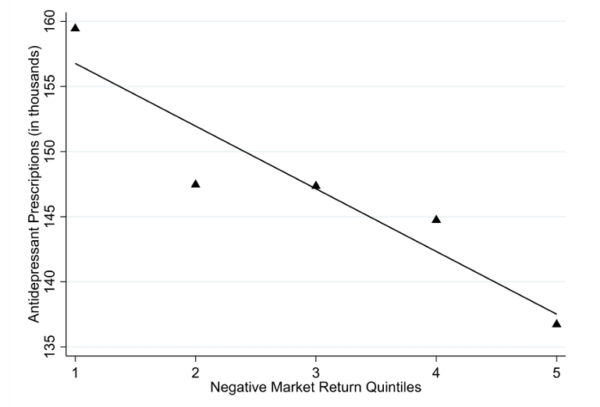

To measure investors’ psychological health, they used antidepressant prescription drug claims in the MarketScan data as a proxy for psychological health. The detailed claim data was sourced from over 200 large, self-insured corporations and insurance carriers and covered 2005-06 (the only period data was available for) and 13,344,000 individuals. Their focus was on those aged 35 to 65—those older were not in the database, and those younger tended not to have much invested in equities. Because the manifestation of depression symptoms, potentially triggered by fluctuations in the stock market, tended to be gradual rather than immediate, they used a two-week lag between market fluctuations and the filling of antidepressant prescriptions. To account for the potential economic influences on antidepressant usage, they included in their regressions local unemployment rates and wage rates. Following is a summary of their key findings:

- Local stock returns asymmetrically affected an individual’s well-being, aligning with prospect theory (loss aversion)—losses in local stock returns led to statistically significant increases in antidepressant usage and increases in psychotherapy sessions.

- Positive stock returns did not reduce antidepressant usage. However, larger stock market losses caused a greater increase in antidepressant usage (again aligning with prospect theory).

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged and do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index

- There was no significant association between future stock returns and the current week’s antidepressant usage—antidepressant usage was not a predictor of stock market performance.

- Stock returns significantly impacted antidepressant usage in the age 45-54 and 55-64 cohorts, while the effect was insignificant for the younger 35-44 cohort (who tended to have smaller equity holdings).

- Focusing on three conditions commonly linked to depression—insomnia, peptic ulcers, and abdominal pain (irritable bowel syndrome)—downturns in the market were associated with a deterioration in physical health, leading to the need for inpatient treatment.

- There was no significant link between the performance of foreign markets and antidepressant usage among U.S. investors—not a surprising result because U.S. investors tend to exhibit a home country bias and thus tend to have low allocations to international equities.

Their findings led Liu and Fan to conclude:

“Our research underscores that the repercussions of stock market declines may transcend beyond the immediate decrease in wealth due to falling asset prices, with potential long-term health and economic consequences for individuals and communities. It is crucial to consider these multifaceted impacts when assessing the true cost of stock market volatility.”

Investor Takeaways

The evidence demonstrates that during periods when stock prices decline, investors’ depression increases. Given that both theory and empirical research findings demonstrate that depressed and anxious investors tend to demonstrate risk-averse behavior, it suggests that their reluctance to engage in the market could lead to its further deepening (helping to explain momentum in markets), with the potential for a negative feedback loop. Liu and Fan explained:

“The market influences the investor’s mood, and the investor’s mood, in turn, influences the market.” The findings also demonstrate the need for having a well-thought-out, written, and signed investment plan. A financial advisor can add great value by helping develop an investment plan with asset allocation specifically tailored to the individual’s ability, willingness, and need to take risk. The advisor should also educate the investor about the virtual certainty that they will experience long periods of poor performance when equity losses can be steep. Being prepared and limiting equity allocations to the appropriate level based on risk tolerance should greatly minimize the risk of making poor decisions triggered by emotions. And based on the findings we have reviewed, it should also lead to reduced incidences of mental and physical illness.

Larry Swedroe is the author or co-author of 18 books on investing, including his latest Enrich Your Future. For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is based on third party data and may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Third-party information is deemed reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency have approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article. LSR-24-635

About the Author: Larry Swedroe

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.