Investing can take a psychological toll on people.

Remember the COVID-19 crash? The S&P 500 lost over a third of its value in just a little over a month. Or go back to Black Monday, October 19th, 1987, when the Dow Jones lost over 20% in a single day in what still remains the largest one-day drop for U.S stocks in recorded history.

Now go and tell people to invest in stocks, where sure, you have some upside potential, but you could also experience these gut-wrenching crashes.

As an investor, you can expect these crashes to happen, and even trend-following might not come to save you. Now, don’t get me wrong. There’s a lot of troopers out there that could stick to their stock program through thick and thin. But if one of your goals is to help against the possibility of fast drawdowns, tail hedging might just be for you.

CONVEXITY

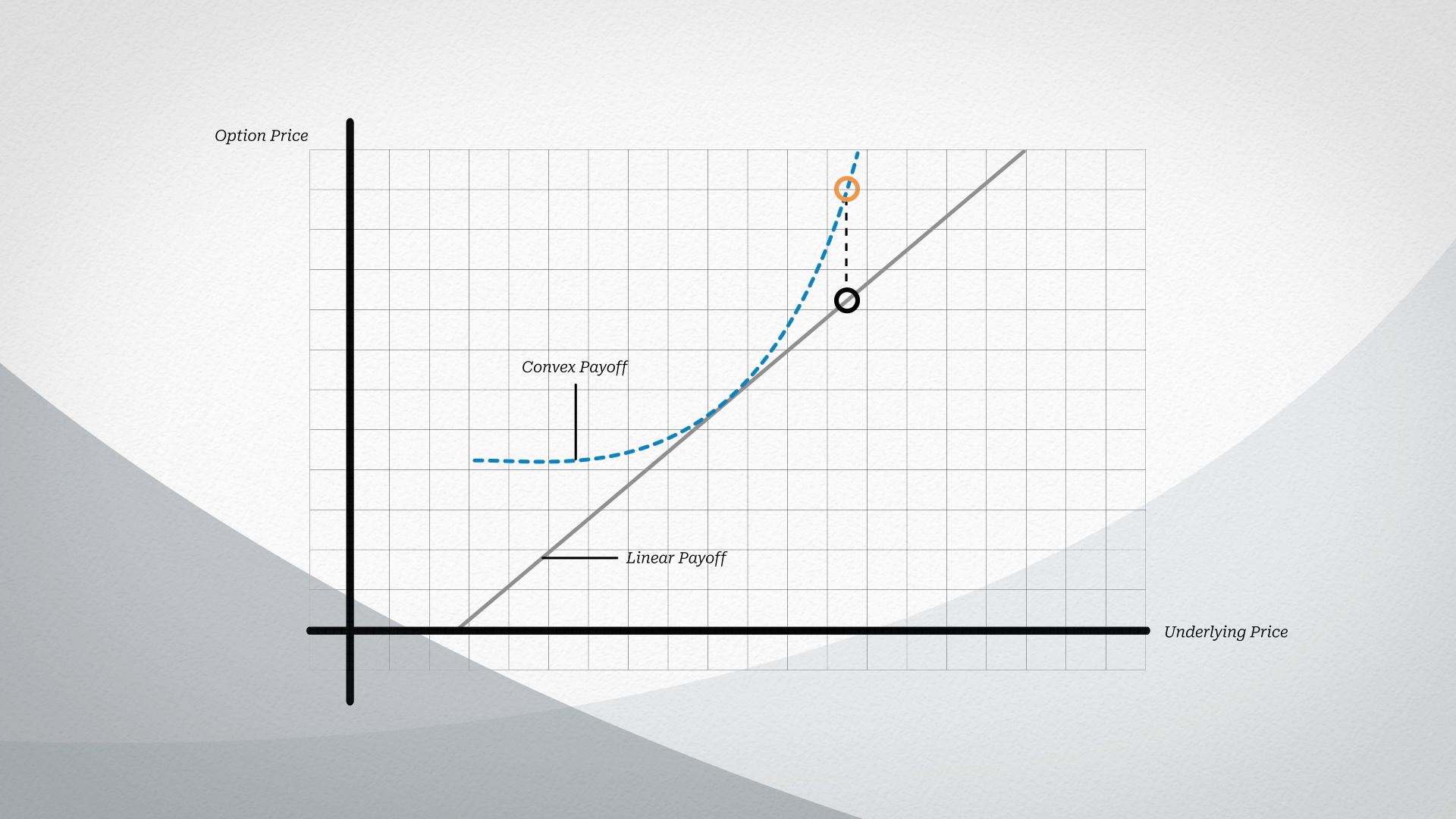

In my last blog post, I talked about convexity in options, or the idea of non-linear payoffs. As options move from out-of-the-money to in-the-money, the returns that follow are not linear but provide accelerating payoffs.

Convexity can then provide explosive payoffs from unlikely events. It’s a powerful weapon to wield, but like most weapons, it could be inefficient or even dangerous in the hands of the untrained.

In this blog post, I’m going to go over three factors that investors should consider when tail hedging.

THE STRIKE PRICE

Most tail hedging strategies share a common approach: they buy out-of-the-money put options on the broader market in an attempt to protect from rapid crashes. But exactly how out-of-the-money should one go?

If you go too far out-of-the-money, the underlying could drop significantly, but the option value might not move enough to offer meaningful protection.

Conversely, if you don’t go far enough out-of-the-money, the strategy’s lack of convexity might dampen the potential returns, thereby providing less protection.

THE TIMING

The second consideration is time-to-expiration. Usually, the shorter the time-to-expiration, the greater the convexity. This should make intuitive sense. The less time to expiration, the less time an option has to move from out-of-the-money to in-the-money. Therefore, if the option does move to in-the-money, the payoff should be greater, all things held equal.

So what expiration should one target?

This introduces a huge issue: path dependency, or the effect that the timing of decisions has on portfolio returns.

As an example, imagine two managers who bought put options at the same time before the COVID-19 drawdown. One of them monetized the puts near the bottom, but the other believed the market would continue falling and held. The first manager would have probably realized jaw-dropping returns. The second manager, though directionally correct when buying, would have realized crummy returns relative to the first manager.

Path dependency effects are also magnified when targeting short-dated options. Consider an investor who owns two put options, one expiring in two weeks and the other expiring in three months. Overall, the longer-dated option has a higher likelihood of being able to catch a risk-off event. Therefore, the shorter-dated option has greater risk of “missing” the risk-off event, but has higher convexity.

Which leads me to the final factor to consider.

THE VOLATILITY

The higher the volatility spike, the more an option’s value increases.

This is what we refer to as vega, or the change in an option’s value for a change in the volatility of the underlying.

For long options, a spike in volatility increases the value of the option, and a drop in volatility decreases the value of the option, all things held equal. This should also make intuitive sense. If an underlying experiences an increase in volatility, there’s more of a chance that it could finish in-the-money.

Consequently, buying put options during drawdowns becomes prohibitively expensive as volatility tends to spike during these crashes. Investors are then left making important risk-reward decisions during highly stressful times: do they buy, hold or monetize?

–

As you can tell, tail-hedging is not as easy as you may think.

First off, it is a highly expensive endeavor. Most of the time, an investor is purchasing put options that simply expire worthless, representing a 100% loss. Even when options are rolled, they become a constant drag on the portfolio – a drag that many would rather avoid, and for good reason.

Secondly, purchasing, timing and monetizing puts can prove to be a highly intellectual and emotional exercise – and one that is extremely hard, if not impossible, to systematize effectively.

But that is tail-hedging for you. A great idea that could reduce portfolio-level risk, but needs careful implementation.

About the Author: Jose Ordonez

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.