As professor John Cochrane observed, the literature on investment factors now fills a veritable “factor zoo,” with hundreds of options. How do investors select from among this huge array of possibilities? In order to minimize the risk that outcomes result from data mining, in our book “Your Complete Guide to Factor-based Investing,” Andrew Berkin and I established six criteria for a factor to be considered for investing. In addition to having provided a statistically significant premium, the premium must have been persistent across time and economic regimes; pervasive across asset classes, countries, regions, and sectors; robust to various definitions; have risk- or behavioral-based explanations for why the premium should be expected to persist in the future; and are implementable (survive transactions costs). While we preferred that the explanation be risk-based (because risk cannot be arbitraged away), we accepted behavioral-based explanations as long as there were identifiable limits to arbitrage that prevented sophisticated investors from correcting mispricings. All six criteria had to be met.

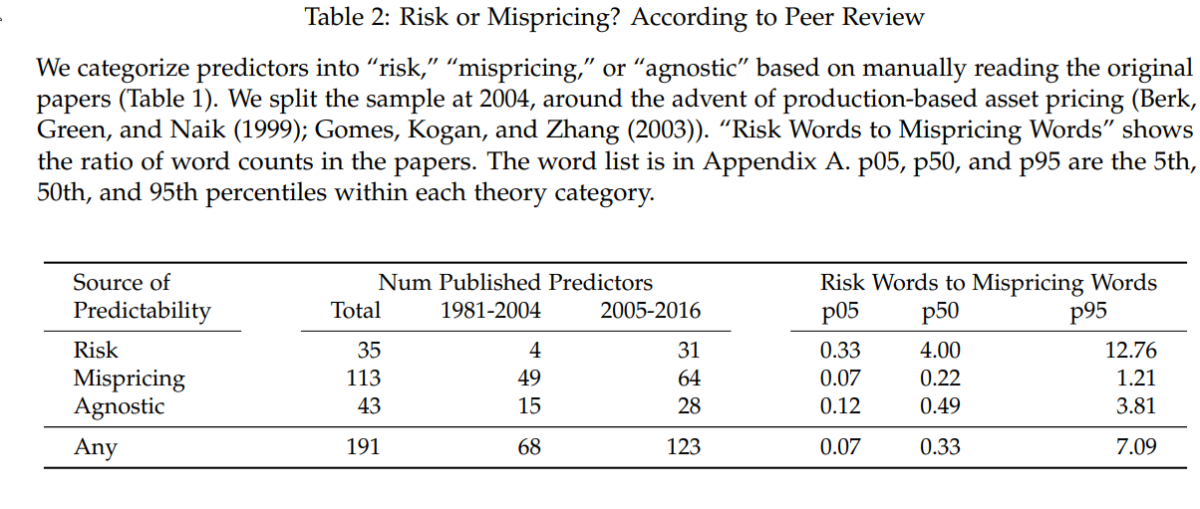

By combining text analysis of publications with out-of-sample tests, Andrew Chen, Alejandro Lopez-Lira, and Tom Zimmermann, authors of the July 2023 study “Peer-Reviewed Theory Does Not Help Predict the Cross-section of Stock Returns,” examined whether financial theory helped predict the cross-section of returns. They read the papers corresponding to 191 published predictors (from the 2022 study “Publication Bias in Asset Pricing Research” by Chen and Zimmermann) and assigned each predictor to “risk,” “mispricing,” or “agnostic” based on the arguments made in the texts. The authors explained:

“Of the 191 predictors we examine, 67% were published in The Journal of Finance, Review of Financial Studies, Journal of Financial Economics, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, Review of Finance, or Management Science. 22% were published in top accounting journals (The Accounting Review, the Journal of Accounting and Economics, the Review of Accounting Studies, and the Journal of Accounting Research). The remaining 11% were published in a wide variety of economics, finance, and accounting journals, including the Journal of Political Economy, Quarterly Journal of Economics, and Review of Economic Dynamics.”

They began by noting:

“If risk-based theory helps us understand expected returns, then risk-based predictability should persist out-of-sample. At the very least, predictability that peer review attributes to risk should be more persistent than predictability derived from pure data mining.” They added: “Economic theory should restrict this set in a way that tilts toward true predictability and therefore limits the impact of selection bias. Peer review further restricts the set of theories, as only the best theories should make it into the top finance journals.”

To address the data mining question, they compared the out-of-sample returns of risk-based theory to those from naive data mining by 29,000 trading strategies formed by sorting stocks on simple functions of 242 accounting variables. They explained:

“These strategies were formed by (1) dividing one variable by another or (2) taking first differences and then dividing, where the denominators were restricted to be variables that are positive for more than 25% of firms in 1963. Despite the complete lack of economics in this data mining exercise, we find this procedure generates substantial ‘out-of-sample’ returns. Sorting strategies into quintiles based on past returns each year and then trading the bottom quintile earns 50 bps per month, implying thousands of strategies with meaningful out-of-sample returns.”

Following is a summary of their findings:

- Based on the original texts, only 18% of predictors were attributed to risk-based theory, 59% were attributed to mispricing, and 23% had uncertain origins.

- Post-publication, risk-based predictability decayed by 65% (p-value < 0.1%) compared to 50% for non-risk predictors.

- Out-of-sample, risk-based predictors failed to outperform data-mined accounting predictors that were matched on in-sample summary statistics.

- Risk-based predictability decayed quickly out-of-sample. In the first five years out-of-sample, the trailing five-year return plummeted, from 150 basis points (bps) per month to 75 bps; 10 years out-of-sample, the trailing mean return dropped to 12 bps, and it hovered near zero for the rest of the out-of-sample. Data-mined returns hovered around 25% of their in-sample means—using risk-based theory was no better than using no theory at all for predicting the cross-section of stock returns.

Because these results were the exact opposite of what is implied by asset pricing theory, Chen, Lopez-Lira, and Zimmermann concluded: “Overall, peer-reviewed research adds little information about future mean returns above naive back testing.” They added: “If anything, the publication of a new risk theory should lead to higher mean returns, as academics teach investors about new risks to avoid.”

This statement implies that researchers suddenly “discover” a risk, and the market becomes more wary. Rather, researchers discover what the market already knows, namely that stocks in certain groups are riskier—and market prices already reflect that risk. In addition, the publication of research about a factor providing a risk-based premium does not necessarily mean that future returns are higher, as investors seek to avoid new risks. The very opposite may be true because risk-seeking investors are now aware of the unique risk factor and could add exposure to that factor not only to earn a premium but also to add diversification benefits. In an efficient market, all risk assets should provide similar risk-adjusted returns. Thus, the publication of a study showing higher risk-adjusted returns should draw cash inflows to eliminate any excess.

Investor Takeaways

Chen, Lopez-Lira, and Zimmermann demonstrated that having a study in a peer-reviewed academic journal that provides a risk-based explanation for a factor premium is insufficient to consider investing in that factor. As mentioned at the beginning of this article, Andrew Berkin and I established that besides providing a premium, all five additional criteria must be met for investors to consider investing in a factor. While one of those is a risk- or behavioral-based explanation, the other four must be met as well. In other words, the risk-based explanation provided by a peer-based review is a necessary ingredient for considering investment, but it is not a sufficient ingredient. All the ingredients are required for investors to be convinced that an outcome is not a result of data mining—under pressure to publish, finance academics may be mining accounting data for return predictability. Forewarned is forearmed.

Larry Swedroe is the author or co-author of 18 books on investing, including his latest Enrich Your Future. For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is based on third party data and may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Third party information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency have approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article. LSR-23-598

About the Author: Larry Swedroe

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.