We believe there are cause and effect relationships in the world — and in investing — that hold true over time. Many are common sense and easily observable – like fire creates smoke – while others are harder to see and understand. With factor investing, true relationships can be hard to see because of randomness and noise in data, and there’s a risk we convince ourselves certain relationships exist that really do not (e.g. smoke creates fire). In much of quantitative finance, data is mined to show a certain effect, but the logic behind the cause and effect relationship is not robust. Then suddenly, because of evidence in noisy historical data, investors begin to believe that smoke creates fire. For us, when historical evidence disagrees with our logic, we always favor applying our fundamental understanding over what a backtest prescribes.

Factor investing is an area we have researched and written about extensively, here, here and here. It is an approach to active management that is lower cost and backed by decades of historical data, compared to the standard high cost, closet-indexing, stock-picking approach, which seems to have failed. But factor investing is still active management (i.e., classic definition of active), and with active management, there is a loser for every winner (at least we think so). Normally the few winners in active management leverage a few key insights that are not recognized by the masses, at least at the time. In contrast, most active management losers tend to copy each other, using the same strategies and managers.

Factor investing is, by its nature, transparent and therefore easily copied. This is why many factor investing strategies are increasingly concerning to us (and this is setting aside the trading cost debate). Data mining, factor crowding, as well as economic changes are all reasons why such strategies may disappoint in the future. We use popular Value and Momentum strategies as examples throughout this thought piece to illustrate these points. Keep in mind, we are not trying to definitively say that such factor strategies do not work, but instead hoping potential users of these strategies will pause and ask deeper questions about them.

To summarize the key points up front:

- Data mining is a huge risk with risk factor-based investment strategies. Many factors have proven to not work in practice and even the most popular factors, like Value and Momentum, may prove less effective going forward.

- Crowding in factor strategies, changes in the economy, and new business models, may eliminate any potential excess return from simple screening metrics that form the basis for many factors.(1)

- Investors can avoid being fooled by backtests by always keeping in mind that most attempts to beat markets will fail because trading is a zero-sum activity.

Data mining is a risk even with Value and Momentum strategies

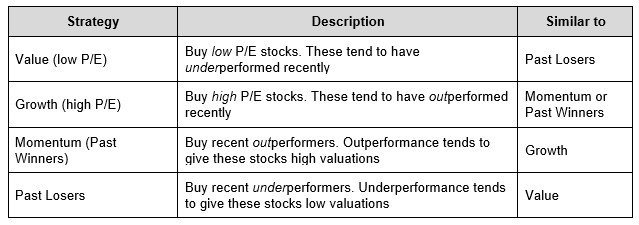

Value is the buying of “cheap” assets, at least based on measures such as a low price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio for stocks. This is the opposite of Growth, or high P/E stocks, which are statistically expensive. Typically, the way a stock becomes relatively cheap is by underperforming in the recent past, and vice versa for Growth stocks. Momentum strategies can be compared similarly. Past winners (Momentum stocks) is about buying stocks that have recently outperformed on the basis that their trend will continue. The opposite is Past Losers (or low momentum).

The table below summarizes these four strategies and how they logically relate to each other:

But the logic explained above is at odds with the academic research backed by decades of market data across time and geography. The below summarizes the difference between what the backtests say versus logic. Both cannot simultaneously be true. Smoke cannot both be created by fire (logical) and produce it (evidence from backtests).

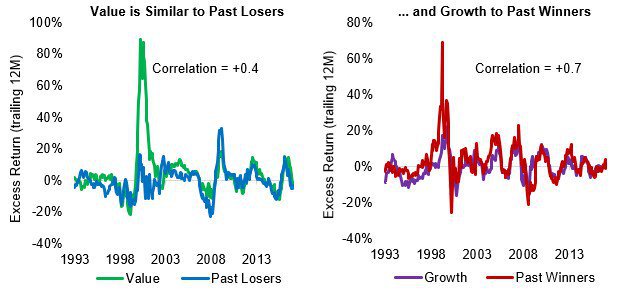

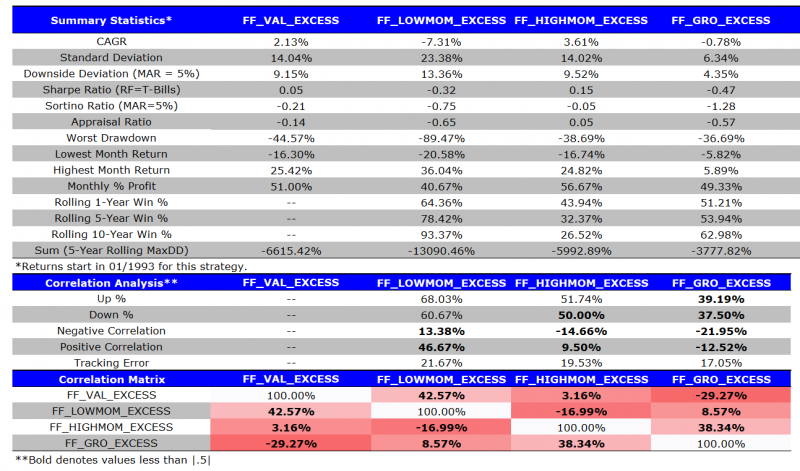

If our logic is correct, then we should see that Value is highly correlated to Past Losers and same for Past Winners (Momentum) and Growth. To test, we simulate portfolios over the last 25 years where Value is defined as the ⅓ of the market with lowest P/E, Growth is ⅓ of the market with the highest P/E, Past Winners (high momentum) is the ⅓ of the market with best trailing 200-day returns, and Past Losers is the ⅓ of the market with the worst trailing 200-day returns. We use the Bloomberg equity database to simulate, but our results are similar to what we find in the commonly used Ken French Data Library. Some might ask why test over only 25 years when there is more data available. Markets and economies change and adapt to new information. While we have tested these strategies going back to the 1920’s, more recent data is more relevant to today’s market conditions, which we also discuss later in this paper. Note, our results are less applicable to more focused factor strategies, where the definitions of value and momentum are associated with top decile stocks.(2)

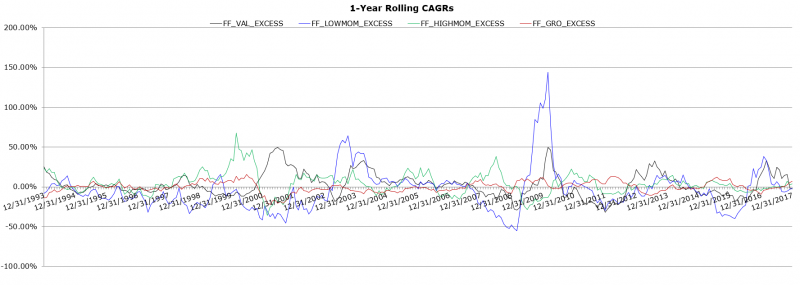

The charts below compare the returns over rolling 12-month periods for Value versus Past Losers, and Momentum versus Growth. To isolate the impact of Value, Growth, Momentum, and Past Losers, we subtract returns of the S&P 500 from them to isolate their excess return.

Two things stand out:

- First is that our logic appears roughly correct. There is a high correlation between Value and Past Losers most of the time, as well as with Growth to Momentum. This partly explains why Value and Momentum are negatively correlated: they select for opposite segments of the market (i.e. Value and Growth should be negatively correlated).

- Second, most of the return difference between the strategies was during a single, isolated market event, the Dot.com bubble and bust of 1998-2002. This was an anomalous period in markets when any strategy that was underweight technology stocks outperformed. Outside of this period, these strategies mostly delivered tracking error relative to a broad index like the S&P 500.

Source: Bloomberg, Greenline Partners analysis. The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Additional information regarding the construction of these results is available upon request.

Selecting a stock based on a high P/E ratio is clearly different than selecting one based on its recent past performance. That is the point here. Despite these differences, the nature of their excess returns is similar and therefore concerning. For example, Past Winners selects solely based on past price moves and is a high turnover strategy (4-8x/yr). Value, on the other hand, selects based on accounting measures, like earnings, and is relatively low turnover (<1x/yr).

As an aside, this suggests it may be better to define the Value Premium as long low P/E stocks (Value) and short Past Losers, instead of the traditional definition of long Value and short Growth. This alternative construction would extract any premium from selecting cheap assets based on valuation instead of past price performance. Similarly, the Momentum Premium may be better defined as long Past Winners and short Growth stocks. A topic for further study.

This pattern of factor strategies outperforming during extreme market periods also supports our prior research that they are best used as screens to help avoid losers.

Combining Value and Momentum has episodic outperformance versus Value alone

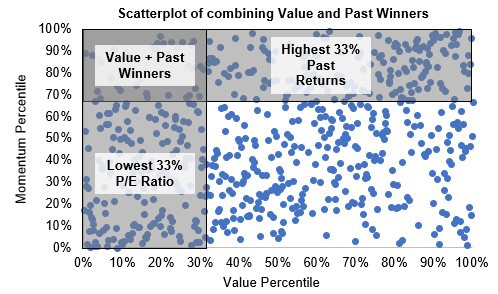

If Momentum (Past Winners) is similar to Growth, then combining Value and Momentum should not be a good idea, as they will cancel each other out. Put another way, combining Value and Growth is like buying the whole market.

To illustrate, we simulate a portfolio that is a sequential combination of Value and Momentum (we know there are multiple techniques for combining both factors, but other methods give a similar conclusion).

The chart below sorts the universe of 500 equities in the S&P 500 along their Value and Momentum scores to show how the Combined portfolio is derived.

Source: Bloomberg, Greenline Partners analysis. The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Additional information regarding the construction of these results is available upon request.

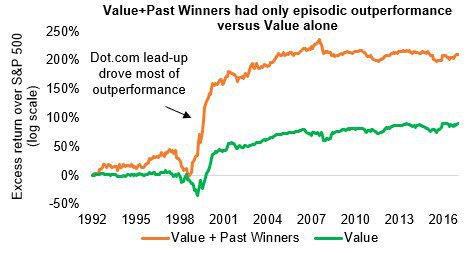

The chart below compares the excess returns over the market of the Value + Past Winners to Value alone. While the cumulative returns of the combined factor portfolio look amazing, we can see that its returns were largely isolated to the Dot.com period.

Source: Bloomberg, Greenline Partners analysis. The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Additional information regarding the construction of these results is available upon request.

Source: Bloomberg, Greenline Partners analysis

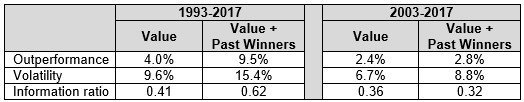

We show the summary statistics below both since 1993, but also since 2003, to show that since the end of the Dot.com period, the risk-adjusted performance of Value + Past Winners has actually been worse than using Value alone.

Source: Bloomberg, Greenline Partners analysis. Outperformance calculated as excess return over S&P 500. The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Additional information regarding the construction of these results is available upon request.

Again, our point here is only to provide food for thought on the topic of whether certain risk factor premia exist and what expectations one should use for their returns going forward. Based on their returns having largely been determined by a few historical events, a zero expected return for these factor premium would be a reasonable starting point. In the end, alpha is a zero-sum game, and never in history has a simple strategy, copied by the masses, generated meaningful outperformance. By definition, it cannot.

There are additional changes in the economy and markets that further weakens the basis for risk factor strategies, which we discuss next.

Past performance is not a guarantee of future results, especially when backtested

We purposely picked only the past 25 years for our simulations in the first section of this paper. This was around the time academics like Eugene Fama, Ken French, Joseph Lakonishok, and others, published their seminal papers on the Value and Momentum effects for the world to see. Since that time, many billions of dollars have been put to work in these strategies. Markets by their nature tend to price in new information and we cannot ignore this fact.

Crowding may reduce returns

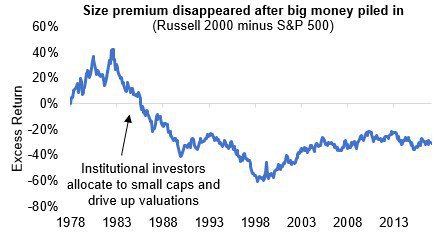

Crowding with risk factor strategies is a topic we and others have commented on in the past.(3) One example of this is the elimination of the size premium (although this is debatable). Logic says that smaller companies should, on average, outperform larger ones to compensate for their higher risk. But since institutional investors began making strategic allocations to this asset class in the early 1980’s, this size premium disappeared, as shown in the chart below of the excess return of small-cap stocks minus large-cap stocks.

Source: Bloomberg, Greenline Partners analysis. The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Additional information regarding the construction of these results is available upon request.

This crowding effect will negatively impact all factors returns as now hundreds of billions of dollars or more are now deployed in these strategies. And we will only be able to definitively measure this impact many years down the road.

Of course, Wes brought to my attention that there is an interesting counter-argument to the crowding argument. Crowding will decrease factor premiums if the capital deployed into these approaches is permanent. If the capital chasing factors is not permanent and is more short-term performance focused, there is the potential that more factor investors could increase the value and momentum premiums. See here for a review of a paper that discusses this topic.

Changes in the economy may reduce the effectiveness of certain factor definitions

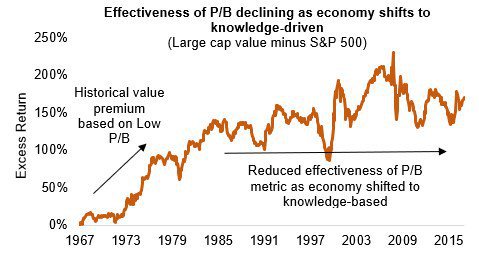

Just as markets adapt and evolve, so does business and the economy. As one example, the US economy has transitioned from being dependent on manufacturing and physical capital to one dependent on intangible knowledge capital in services and technology businesses over the last few decades. This means an increasing amount of the average company’s value is no longer reflected in their financial statements. Today, intangibles like intellectual property and proprietary data, are of great value but generally not recorded on a balance sheet, potentially reducing the effectiveness of a measure such as book equity value.

This change in our economy explains why the price-to-book equity (P/B) measure has been ineffective for selecting value companies for over 30 years.(4) The chart below shows the cumulative returns of Value, as measured by low P/B, since 1965. We can see its performance relative to the market has become largely ineffective since the early 1980’s, something others have confirmed as well.(5)

Source: Ken French Data Library, Bloomberg, Greenline Partners analysis. The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Additional information regarding the construction of these results is available upon request.

Valuation is the anchor for markets, but it is complex. Using simple metrics like price-to-earnings ratios is only a shortcut, but one that has statistically worked, at least historically. In practice, any factor that measures the growth rate and quality of underlying cash flows should be factored into the valuation. And as accounting rules change and as business models evolve, this will all determine the effectiveness of metrics that worked in the past.

To Avoid Mistakes, Have the Right Framework

In this era of big data and cheap computing power, it is easy for anyone to create a winning investment strategy in a backtest. But investing is forward-looking and markets are adept at pricing in known information. Often, a strategy has a one-off experience that drives its outperformance, which is masked in summary statistics. We see this in risk factor strategies, even Value and Momentum. If these one-off events do not repeat, most factor strategies are at risk of being ineffective going forward. There are arguments that open secrets like value and momentum can continue to work out of sample, and I invite you to read the sustainable active investing framework, for these arguments.

What’s the bottom line? Investing is complex, and there is always more randomness and more noise than signal in the data we observe. Managers who outperform, even over long periods of 10 years, often do not repeat their feat. We think applying a few logical principles to this complex problem can help cut through the noise. Two such principles we apply are that markets are hard to beat (since trading is a zero-sum), even before fees and trading costs; and always favor a logical explanation over statistics.

“Organized common (or uncommon) sense is an enormously powerful tool. There are huge dangers with computers. People calculate too much and think too little.” — Charlie Munger

References[+]

| ↑1 | Counter point here |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Here are the summary stats for the top decile value/growth and top decile winner/loser value-weight portfolios using Ken French data.

First, the summary statistics. Note the low correlation on the portfolios.

And here is the rolling 12-month analysis:

|

| ↑3 | “Factor Investing: Fundamentally Sound or Short-term Fad?” Greenline Partners, May 2017 |

| ↑4 | The counter is that the ineffectiveness of p/b is driven by an outlier event in 2008, among other things. See here for a discussion. Also important to note is that the large cap value premium has never existed |

| ↑5 | Fama, Eugene F. and Kenneth R. French, 2012. “Size, Value, and Momentum in International Stock Returns”. Journal of Financial Economics 105, 457-472. |

About the Author: Maneesh Shanbhag

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.