Does Herding Behavior Reveal Skill? An Analysis of Mutual Fund Performance

- Hao Jiang and Michela Verardo

- The Journal of Finance, Fall 2018

- A version of this paper can be found here

- Want to read our summaries of academic finance papers? Check out our Academic Research Insight category.

What are the Research Questions?

- Can investors identify skilled and unskilled mutual fund managers by observing their tendency to herd?

- Do differences in herding behavior across funds predict mutual fund performance?

- Does skill drives the link between herding and future performance?

- Does herding reduce the probability that inexperienced managers are terminated?

What are the Academic Insights?

The authors test a comprehensive sample of more than 2255 active equity funds domiciled in the US between 1990 and 2009. Their results are as follows:

- YES- The authors develop a measure of fund herding based on the intertemporal correlation between the trades of a given fund and the collective trading decisions that institutional investors have made in the past. This measure of herding captures a fund’s tendency to imitate the past trading decisions of the crowd. The fund herding

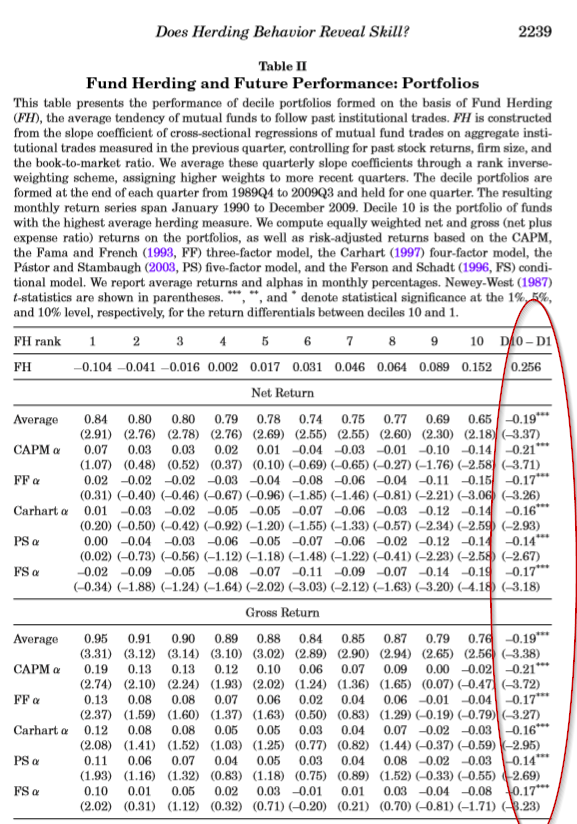

reveal a large degree of heterogeneity in herding behavior, with some funds exhibiting a tendency to follow the crowd while others show a propensity to trade in the opposite direction. - YES- The differences in fund herding have strong predictive power for the

cross section of mutual fund returns. The top-decile portfolio of herding funds underperforms the bottom-decile portfolio ofantiherding funds by 2.28% on an annualized basis, both before and after expenses. The authors obtain similar results when we account for exposures to factors such as the market risk premium, size, value, momentum, and liquidity: the alphas from different multifactor models vary between1.68% and 2.52% on an annualized basis. - YES- The authors conduct a number of tests to deepen their understanding of the link between heterogeneity in herding behavior and skill. For example, they analyze the performance of mutual funds’ investment choices for the subset of stocks that are not heavily traded by institutions. The results show that stocks that constitute large bets by

antiherding funds outperform stocks held mostly by herding funds: the difference in returns is large and significant, with an average Carhart alpha of 38 bps per month.Antiherding fundstherefore make better investment decisions than their herding peers, even on stocks that are not subject to potential price pressure caused by institutional herds. Additionally, the authors examine time-series variation in the performance gap between herding andantiherding funds. If differences in skill drive differences in herding behavior, we should observe a widening of the performance gap in times of greater investment opportunities in the mutual fund industry, which skilled funds would be better able to exploit. Using stock return dispersion, average idiosyncratic volatility, and investor sentiment to capture time-varying investment opportunities, the authors find that the performance gap between herding andantiherding funds is indeed significantly larger during and after periods in which opportunities for active managers are more valuable. - YES- The authors find that, as predicted, the negative relation between herding behavior and future performance is stronger for inexperienced managers. This result suggests that, among career-concerned managers, a strong herding tendency reveals

lack of skill,whereas antiherding might signal superior ability in the absence of a sufficiently long performance record.

The authors conduct a series of tests to assess the robustness of the predictive ability of fund herding for mutual fund performance with the aim to show that results are not sensitive to the empirical methodology used to estimate fund herding nor to how they measure fund performance.

Why does it matter?

This study contributes to the literature on mutual fund performance, which seeks to address the challenge of identifying skilled managers in the cross section of mutual funds: herding behavior can a powerful tool to capture the distribution of skill among mutual fund managers. For example, it shows that differences in herding behavior reveal differences in skill for less experienced managers, who cannot rely on a long performance record to signal their ability. The overall results represent an important step toward understanding how incentives shape managerial behavior in the presence of cross-sectional dispersion in skill.

The Most Important Chart from the Paper

Table II presents the portfolio results. The top row reports the average value of fund herding for each decile portfolio, measured at the end of quarter t. Funds in the top decile exhibit a strong tendency to follow past institutional trades, with mean values of fund herding reaching 15.3%, whereas funds in the bottom decile exhibit anti-herding behavior, with large and negative values of fund herding reaching −10.4%. Fund returns are measured in each month of quarter t+1. The panel for net returns shows that, in the quarter following portfolio formation, the funds with the highest herding tendency in decile 10 underperform the funds with the highest

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged and do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index.

Abstract

We uncover a negative relation between herding behavior and skill in the mutual fund industry. Our new, dynamic measure of fund-level herding captures the tendency of fund managers to follow the trades of the institutional crowd. We find that herding funds underperform their anti-herding peers by over 2% per year. Differences in skill drive this performance gap: anti-herding funds make superior investment decisions even on stocks not heavily traded by institutions, and can anticipate the trades of the crowd; furthermore, the herding-

antiherding performance gap is persistent, wider whenskill is more valuable, and larger among managers with stronger career concerns.

About the Author: Wesley Gray, PhD

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.