As far back as 1976, with the publication of Fischer Black’s “Studies of Stock Price Volatility Changes” financial economists have known that volatility and returns are negatively correlated. This relationship results in the tendency to produce negative equity returns in times of high volatility. In addition, the research, including the 2017 study “Tail Risk Mitigation with Managed Volatility Strategies,” demonstrates that while past returns do not predict future returns, past volatility largely predicts future near-term volatility, i.e., volatility is persistent (it clusters). High (low) volatility over the recent past tends to be followed by high (low) volatility in the near future. Taken together, these findings have led to the development of strategies that scale volatility inversely to past realized volatility, with the strategies tending to produce a positive impact on investment performance.

Research Findings

The authors of the 2018 study “The Impact of Volatility Targeting” examined the impact on 60 assets, with daily data beginning as early as 1926 and ending in 2017. They not only confirmed that risk assets exhibit a negative relationship between returns and volatility but also found that in addition to reducing volatility, scaling reduces excess kurtosis (fatter tails than in normal distributions), cutting both tails—right (good tail) and left (bad tail). And for portfolios of risk assets, Sharpe ratios (measures of risk-adjusted return) are higher with volatility scaling. Another key finding was that since volatility often increases in periods of negative returns, targeting volatility causes positions to be reduced, which is the same direction one would expect from a time-series momentum (trend-following) strategy.

These findings are consistent with those of other research, including the 2017 study “A Century of Evidence on Trend-Following Investing” the 2019 studies “Volatility Expectations and Returns” and “Portfolio Management of Commodity Trading Advisors With Volatility Targeting,” and the 2020 study “Understanding Volatility-Managed Portfolios.” However, these findings are contrary to traditional finance theory and the intuition that the standard risk-return tradeoff should lead to underperformance of a portfolio that scales down exposure during volatile periods. The strategy has worked because volatility clusters and historically increased volatility have not been compensated by higher returns.

Latest Research

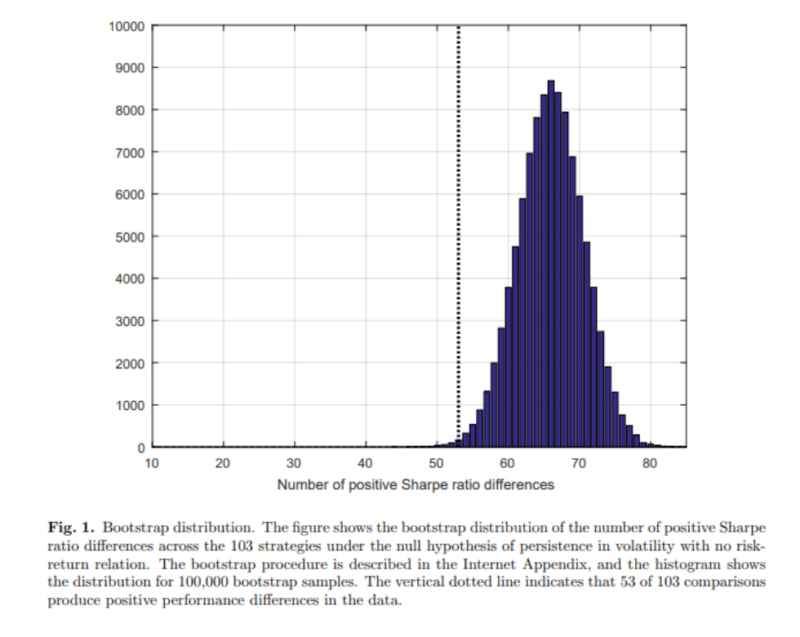

Scott Cederburg, Michael O’Doherty, Feifei Wang, and, Xuemin Sterling Yan contribute to the literature on volatility managed portfolios with their study “On the Performance of Volatility-Managed Portfolios,” published in the October 2020 issue of the Journal of Financial Economics. (also covered here by Tommi). Using a comprehensive set of 103 equity strategies, they analyzed the value of volatility-managed portfolios for real-time investors. The nine factors analyzed were the market (MKT), size (SMB), and value (HML) factors from the Fama-French (1993) three-factor model; a momentum factor (MOM); the profitability (RMW) and investment (CMA) factors from the Fama-French (2015) five-factor model; the profitability (ROE) and investment (IA) factors from the Hou-Xue-Zhang (2015) q-factor model; and Frazzini and Pedersen’s (2014) betting-against-beta (BAB) factor. They generated 100,000 bootstrap samples, ran 103 direct performance comparisons in each bootstrap sample, and counted the number of positive performance differences. They then compared the number of positive differences in the data to the bootstrap distribution under the null hypothesis to assess statistical significance. Following is a summary of their findings:

- Volatility-managed portfolios do not systematically outperform their corresponding unmanaged portfolios in direct comparisons—they do not systematically produce higher Sharpe ratios.

- The volatility-managed versions outperformed in 53 out of 103 cases, and only eight strategies yielded consistently higher Sharpe ratios in favor of volatility management—consistent with prior research, the eight cases were concentrated among momentum, profitability, and betting-against-beta strategies. Nevertheless, there is little statistical or economic evidence for volatility management in other factors.

- Consistent with prior research findings, volatility-managed portfolios tend to exhibit significantly positive alphas in spanning regressions. However, the trading strategies implied by these regressions are not implementable in real-time (because the optimal weighting of scaled and unscaled portfolios depends on in-sample return moments, the required strategy is not known prior to the end of the sample), and reasonable out-of-sample versions generally earn lower certainty equivalent returns and Sharpe ratios than do simple investments in the original, unmanaged portfolios.

- The result is driven by substantial structural instability in the underlying spanning regressions for these strategies.

The authors noted that volatility management is likely to be successful if volatility is persistent (which is the case for momentum, but not necessarily for other factors) and the risk-return relation is flat (which it is). Thus, their finding that volatility management is successful in momentum strategies should not be a surprise.

Their findings led the authors to conclude:

“Overall, our findings suggest a more tempered interpretation of the practical value of volatility-managed portfolios relative to prior literature.”

Summary

Recent literature has suggested that investors can enhance Sharpe ratios and lifetime utility by adopting simple trading rules that scale positions in equity portfolios by lagged variance. Cederburg, O’Doherty, Wang, and Yan demonstrated that while volatility management does enhance the performance of momentum (in particular), profitability, and BAB strategies, it has not added value when used with the other six commonly used factors. In other words, they are not a panacea to improve all factor-based strategies.

Disclosures

Important Disclosure: The opinions expressed by featured authors are their own and may not accurately reflect those of Buckingham Strategic Wealth®. This article is for general information only and is not intended to serve as specific financial, accounting, or tax advice. R-20-1568

© 2020 Buckingham Strategic Wealth

About the Author: Larry Swedroe

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.