At the table but cannot break through the glass ceiling: Board leadership positions elude diverse directors

- Laura Casares Field, Matthew E. Souther, Adam S. Yore

- Journal of Financial Economics

- A version of this paper can be found here

- Want to read our summaries of academic finance papers? Check out our Academic Research Insight category

What are the research questions?

Quite a bit of research has been conducted on the representation of minorities and/or women in the boardroom. However, there is less research on how much diversity there is among board leadership. Board leadership is important because these individuals are responsible for setting the agenda and direction of the board itself. The research under discussion examines the degree to which women and minorities serve in leadership roles. With a large universe of 19,686 individual, nonemployee directors serving on 2,254 unique US corporate boards, the authors are able to examine the complete set of candidates for a specific leadership board position. The extensive nature of the universe permits the comparison of characteristics of directors appointed as board leaders to those that are not so appointed. The article is quite detailed. The major research questions are as follows:

- Has the status of female and minority board representation and corporate diversity policies changed over the 2006-2017 period studied?

- Are there any board leadership positions whereby diverse directors are well represented?

- Do diverse directors serve on multiple boards instead of pursuing leadership roles?

- Can the underrepresentation of diverse directors in leadership board roles be attributed to a lack of effectiveness as a “monitor”?

- Are diverse directors valued by shareholders at the ballot box?

What are the Academic Insights?

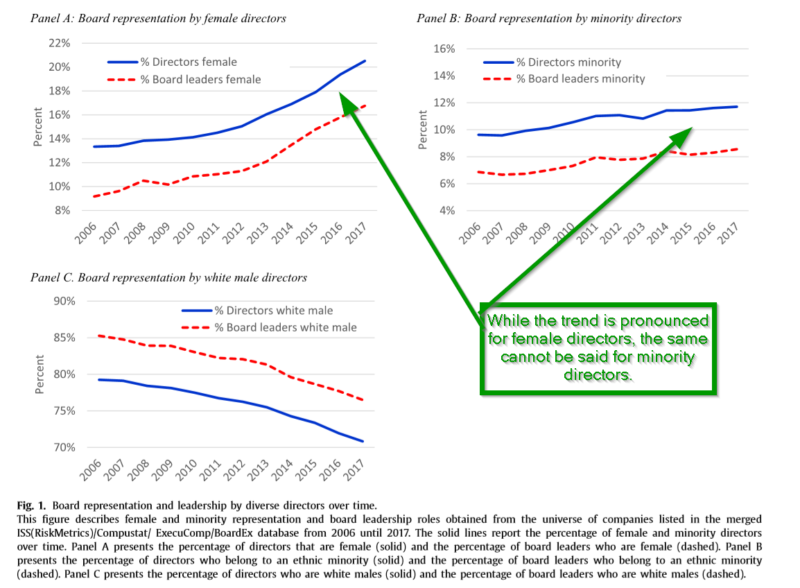

- YES. Relative to the general population, the representation of women and minorities have increased although they remain underrepresented. In 2006, 71% of boards included at least one female, rising to 88% in 2017. For minorities, the corresponding values are 50% and 59%. However, for director leadership positions, women comprise 17% and minorities 9% as of 2017. For context, note the possible pool of director-material corporations have to choose from: women (minorities) represent 51% (34%) of the general population; the number of female graduates with a four-year college degree has exceeded that of males since 2014, while 28% were minorities; among doctorates, 53% were women. As to policy, the results should be considered with respect to the 2010 SEC Proxy Disclosure Enhancements mandating corporations to communicate how diversity is included in the director nomination process, if at all. Before the SEC mandate, 9-10% of corporations included a diversity policy in proxy statements, increasing to 48.8% by 2017.

- NO.

- CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD or LEAD DIRECTORS: Women and minorities are 3.6% less likely to serve as chairman of the board and 5.2% less likely to serve as lead director. When applied to an average board of 9 directors, the authors suggest that these values correspond to decreases in the likelihood of service in one of these key leadership positions falls in the range of 32% to 47%.

- COMMITTEE CHAIRS: On average, diverse directors are 8.8% less likely to serve in these positions. With respect to the 4 individual committees considered (compensation, audit, nominating, governance), diverse directors are negatively (with significance, 1%) related to the probability of serving as nonexecutive chairman, lead director, audit chair, with the strongest effect being the chair of the compensation committee. This was true for every year of the sample. For nominating and governance, the effect was significant at the 5% and 10% for almost every year of the sample. When gender is considered separately from minority status, the results are similar for women being appointed as chairs of the audit and compensation (again the strongest effect) committees, but not significantly different for being appointed as chairs of the governance and nominating committees. For minorities, the overall probability of serving as a chair of any committee is 12% lower than for non-minorities. Again, the strongest effect was for the compensation committee. Caveat: the results presented in this section were robust to varying test specifications.

- NO. Diverse directors are less likely than non-diverse directors to serve as board leaders, even if they do not have any outside board appointments. Here are the details: With no outside appointments and when compared to non-diverse directors, they are 7.2% less likely to serve as chairman or lead; 2.4% less likely to serve as an audit chair; 3.2% less likely to serve as compensation chair; and 1% less likely to serve as nominating or compensation chair. With one outside appointment and tenure of at least 5 years, diverse directors are less likely to serve as chairman or lead at 8.8%, as audit chair at 1.6%; as compensation chair at 3.6%; and as nominating chair at .9%. With service on at least 3 appointments, the numbers are similarly less likely. Robustness tests indicate these differences survive controls for qualifications, risk aversion and geographic location.

- NO. The authors find no evidence that diverse directors exhibit less monitoring skill when compared to their non-diverse counterparts. Monitoring, actually an unobservable skill, is measured in this and previous research along several dimensions including CEO turnover, executive compensation, earnings quality and fraud prevention. No significant differences between diverse and non-diverse chairmen or lead directors with respect to executive compensation. It did appear that forced CEO turnover for poor performance was higher with more diversity on the board. Although diversity on the audit committee had no effect on reported earnings one way or the other, the authors reported a reduction in discretionary accruals was associated with a greater percentage of diversity of directors.

- YES. Shareholders appear to place a premium on the services provided by a diverse set of director candidates. Female and minority candidates exhibited positive and significant effects from shareholder votes when compared to their counterparts. A slight positive trend was also observed across the sample period.

Why does it matter?

This research raises new questions and issues regarding board inequality. In contrast to most research that documents the paucity of women and minorities appointed to boards of directors, this research points to the presence of a leadership gap even after women and minorities have been appointed to boards in significant numbers. The authors argue that this leadership gap in diversity on corporate boards persists in spite of increasing diversity representation. Despite the evidence that diverse directors exhibit equivalent or superior qualifications, skills, and experience, and perform leadership duties as well as their non-diverse counterparts, appointments to key leadership board positions do not accrue. Simply increasing the percentage of women and minorities in board composition does not do the trick. Without policies that overtly promote diversity and especially including diverse directors on nominating committees, the leadership gap will persist.

The most important chart from the paper

Abstract

We explore the labor market effects of gender and race by examining board leadership appointments. Prior studies are often limited by observing only hired candidates, whereas the boardroom provides a controlled setting where both hired and unhired candidates are observable. Although diverse (female and minority) board representation has increased, diverse directors are significantly less likely to serve in leadership positions, despite possessing stronger qualifications than non-diverse directors. While specialized skills such as prior leadership or finance experience increase the likelihood of appointment, that likelihood is reduced for diverse directors. Additional tests provide no evidence that diverse directors are less effective.

About the Author: Tommi Johnsen, PhD

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.