There are several significant, well-documented benefits of index funds. In addition to outperforming a large majority of actively managed funds, they tend to have low fees, low turnover (resulting in low trading costs and high tax efficiency), broad diversification, high liquidity, and near-zero tracking error (generally assumed to mean that they incur negligible trading costs). However, there are some negatives of index replication strategies:

- Sensitivity to risk factors that varies over time. Because indexes typically reconstitute annually, they lose exposure to their asset class over time as stocks migrate across asset classes over a year.

- Forced transactions (to avoid tracking error) as stocks enter and leave an index, resulting in higher trading costs.

- Risk of exploitation through front-running. Active managers can exploit the knowledge that index funds must trade on specific dates.

- Inclusion of all stocks in the index. Lottery-like stocks (such as “penny” stocks, stocks in bankruptcy, and small growth stocks with high investment and low profitability) have historically produced poor risk-adjusted returns.

- Limited ability to pursue tax-saving strategies, including intentionally avoiding taking any short‐term gains and offsetting capital gains with capital losses.

Most investors are likely unaware that many of the trading costs of index funds are hidden, as they are already embedded in the published index—the forced trading costs (price impact) equally affect the performance of the index fund and the index against which it is measured. Through intelligent design, systematic (quantitative) structured portfolios can either minimize those negatives or eliminate them. For example, to maintain more consistent exposure to the factors the index is exposed to (such as size, value, and profitability/quality) and thus capture more of the premium, instead of rebalancing annually, structured portfolios can be reconstituted more frequently (such as monthly, or quarterly for higher turnover strategies such as momentum). They can also avoid forced transactions as stocks enter and leave indices by implementing buy-and-hold ranges. And they can trade ahead of index funds and/or delay reconstitution trades. They can also trade patiently, using algorithmic programs to minimize market impact costs. In addition, a systematic, structured portfolio can exclude lottery stocks by using a filter to screen them all out.

Empirical Evidence

Robert Arnott, Christopher Brightman, Vitali Kalesnik, and Lillian Wu, authors of the study “Earning Alpha by Avoiding the Index Rebalancing Crowd,” explored alternative (to the S&P 500 Index) index rules to help investors mitigate the negatives of pure index replication strategies. They began by noting: “Whenever an index rebalances or makes changes to its constituents, the added stocks are routinely priced at a substantial premium to market valuation multiples (i.e., the index buys high), whereas discretionary deletions (except for removals related to mergers, acquisitions, and other corporate actions) are routinely deep-discount value stocks (i.e., the index sells low). Additions tend to be priced at valuation multiples more than four times as expensive as those of discretionary deletions, using a blend of relative price-to-earnings (P/E), price-to-cash flow (P/CF), price-to-book (P/B), price-to-sales (P/S), and (if available) price-to-dividends (P/D) ratios. In other words, conventional cap-weighted index funds generally buy high and sell low.”

Their sample of historical component changes consisted of 1,196 additions and 1,194 deletions from March 1970 to June 2021. Note that beginning in October 1989, the S&P Index Committee began to preannounce changes to the index. Thus, their analysis focused primarily on the period starting October 1989. Over that span, roughly 90% of additions were discretionary, with just 116 being non-discretionary (e.g., company spin-offs and divestitures, such as 3Com spinning off Palm in 2000). In contrast, more than 60% of the index deletions were nondiscretionary (e.g., bankruptcies and mergers). Following is a summary of their findings:

- If S&P did not preannounce index changes, the hypothetical index performance would have been better by 20 basis points (bps) a year. In the pre-1989 period, when Standard & Poor’s announced changes in the S&P 500 after the market had closed, with those changes taking effect at the already-known closing price on that day, significant trading-related impact costs showed up as slippage against the theoretical index.

- Additions to the index, based on an average of P/B, P/E, P/CF, P/S, and P/D, were 92% more expensive than the market. In comparison, the discretionary deletions were 55% cheaper than the market based on the combination of five relative valuation measures.

- In the year before the announcement that they were being added to the S&P 500 Index, new additions outperformed the S&P 500 by an average of 41.5%. In comparison, discretionary deletions underperformed the S&P 500 by 29.1%—a performance gap of over 70%. However, in the year after a change in the S&P 500 Index, discretionary deletions beat additions by 22% on average.

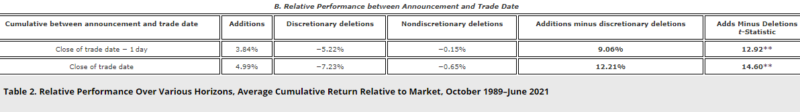

- From the announcement date to the market close on the trade date, additions on average appreciated by another 5.0% relative to the market, while deletions trailed the market by an additional 7.2%—a 12.2% performance gap. On the day after the trade date, there was another 1.2% performance spread in favor of the additions over the deletions, perhaps due to catch-up trades by index funds that did not complete all of their addition and deletion trades on or before the trade date—the 12.2% performance spread between additions and deletions grew to 13.4%. There was also a 2.4% gap on the day before the announcement (active investors anticipating the announcement and front running it), which brought the performance gap to 15.8%.

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged and do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index.

- Breaking the 1989-2021 sample into halves, the mean-reversion effect was stronger in the second half of the sample for the additions: -1.2% in the first half of the sample and ‑2.5% in the second, but the opposite was true for the deletions (falling from 31.8% in the first half to 12.3% in the second). The one-year spread between additions and deletions was 33.0% from 1989 to 2004 and 14.8% from 2005 to 2021—index effects declined in the latter part of the sample, which could have been the result of the market becoming more efficient around index rebalancing or perhaps the absence of a value effect during most of the 2005-2021 span.

- Simple rules, such as trading ahead of index funds or delaying reconstitution trades by three to 12 months, could have added up to 23 bps a year. That benefit roughly doubled when they used a cap-weighted portfolio selected based on the fundamental size of a company’s business or its multiyear average market cap.

- The top 500 by fundamental size strategy outperformed the S&P 500 by 46 bps per annum.

- Similar results were found when using the Russell 1000 Index.

Another interesting and perhaps surprising finding was that the S&P 500 had a larger tracking error relative to the top 500 selected by market cap than it did relative to the top 500 selected by the fundamental size of the underlying companies’ businesses.

Their findings led Arnott, Brightman, Kalesnik and Wu to conclude:

“The most important Achilles’ heel for index funds is the very avoidable buy-high/sell-low dynamic of adding recent highfliers and dropping deeply out-of-favor stocks, sometimes near a nadir in price; this effect is considerably larger than the liquidity effect. … Smarter trading strategies that mitigate the indexing world’s self-inflicted buy-high/sell-low travails can add roughly 300 to 1,000 bps of performance a year.”

They added:

“The dirty secret of index fund investing is that the transaction costs are still there and simply hidden in plain sight.”

Investor Takeaways

While index funds offer significant benefits, the strategy of index replication, with a focus on minimization of tracking error, causes them to have some negatives that can be eliminated or minimized by intelligent design and patient trading. Investors willing to accept some degree of random tracking error (you cannot add value without accepting some tracking error risk) can improve the performance of pure index funds. Fund families such as Dimensional have long used such strategies to provide investors with superior products.

Larry Swedroe is head of financial and economic research for Buckingham Wealth Partners.

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is based on third party data and may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Third party information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. By clicking on any of the links above, you acknowledge that they are solely for your convenience, and do not necessarily imply any affiliations, sponsorships, endorsements or representations whatsoever by us regarding third-party websites. We are not responsible for the content, availability or privacy policies of these sites, and shall not be responsible or liable for any information, opinions, advice, products or services available on or through them. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency have approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article. The opinions expressed here are their own and may not accurately reflect those of Buckingham Strategic Wealth and its affiliates. LSR-23-500

About the Author: Larry Swedroe

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.