As pundits wrestle over the cause, implications, and sustainability of the recent massive moves in interest rates, I’ll instead delve into the two terms most often blamed for these shifts in rates: R-star and the Term Structure Premium. Unfortunately, what most want—a measure of them—is unknowable.

But we can benefit from understanding the theories and models behind these terms. We can glean guidance on what we need, namely a better understanding of the risks and rewards of buying longer-maturing bonds at current rate levels. I contend that now is a good time to secure future cash flows by buying bonds, although determining the precise amount to invest remains a challenge.

Pure Expectations Hypothesis and Liquidity Preference Theory

Starting with the basics of bond math, the Pure Expectations Hypothesis assumes that investors are indifferent to holding short versus longer maturing bonds. In other words, they expect the same returns, whether rolling over short-maturity bonds or holding a longer-maturing bond. This indifference implies investors are risk-neutral and are willing to accept the greater inherent price volatility associated with longer maturities.

Based on this assumption, longer-maturity bonds should reflect the combined expectations of short-term interest rates. If interest rates are higher (or lower) for longer-maturity bonds than shorter-maturity bonds, this implies an expectation that short-term rates will increase (or decrease). Using the full yield curve, we can construct what the “market expectations” are for future rates, a terminology often used in the popular press.

But this depiction of exceptions is lazy. Much like Warren Buffet was wrong to equate the embedded pseudo probabilities within option prices as real probabilities, assuming the future market prices of bonds reflect true expectations of their prices is also wrong.(1). Again, future market prices, like option prices, only reflect true expectations assuming risk neutrality. As Gene Fama documents (1976, 1984),(2) and the picture below illustrates, “market expectations” of interest rates embedded in futures alone are also lousy predictors of future interest rates.

![By Apollo’s Torsten Slok, borrowed[/ref] from John Cochrane’s blog “The Grumpy Economist.”](https://alphaarchitect.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Fed-Funds-Rate-vs-Fed-Fund-Futures.jpg)

![Source: Substack.com Erdmann Housing Tracker[/ref]](https://alphaarchitect.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Eurodollar-SOFR-Yield-Curve.jpg)

Of course, interest rate expectations are still reflected in future prices. These prices reflect how the Federal Reserve will likely set future short-term lending rates and are generally accurate in the near-term. Bond prices in the futures market just don’t tell the whole story.

For instance, investors prefer the liquidity of cash over committing their funds over extended periods. Banks, as we saw in March, cannot readily profit from this preference by borrowing short-term via deposits and lending long-term through bond purchases. Banks and investors demand (or, in the bank’s case, should demand!) to be compensated for taking on interest-rate risk, as hypothesized by the Liquidity Preference Theory.

Term Premium

Related, interest rates compensate investors for postponing spending and saving money for the future. As I explain in my 2016 article in this blog, “Interest Rates and Value Investing”, inflation expectations heavily influence that decision, but the “real” interest rate (the nominal rate stripped of inflation expectations) also needs to compensate investors for the risk that their inflation and short-term rate expectations could be wrong. Offsetting those risks, longer-term bonds often increase in value during recessions (or pandemics!), serving as a valuable hedge. All these factors, and more, help set the term premium, the premium investors demand to lock in rates by buying longer maturing bonds instead of sitting in cash or shorter-term bonds. No wonder Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari recently joked, “…that term premium is the economists’ version of dark matter—it’s the residual of all the stuff we can’t explain.”

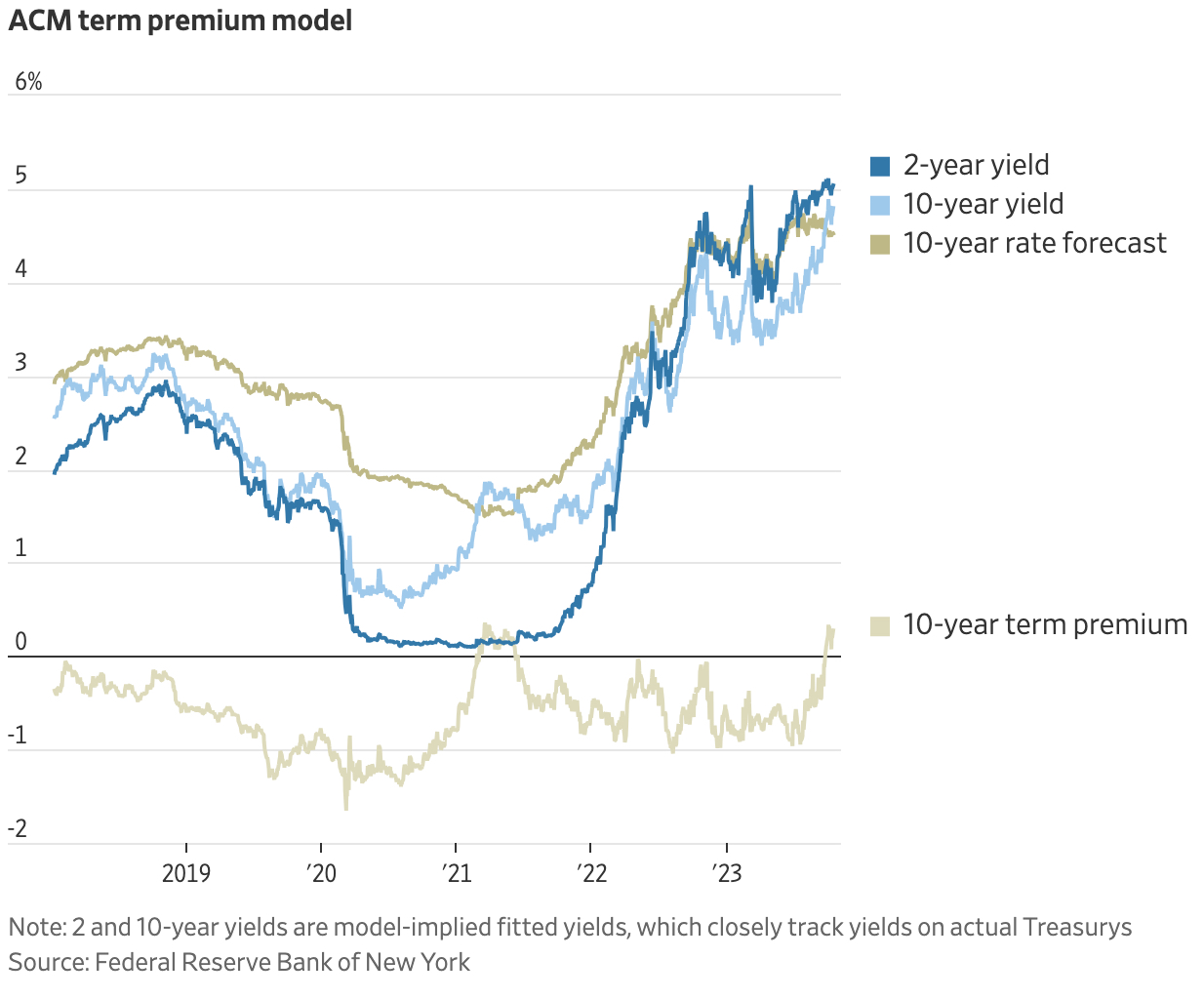

Although we can’t know for sure the factors pushing longer yields up faster than shorter yields, we can make educated guesses. As Sam Goldfarb of the Wall Street Journal explains, the ACM model published by the New York Fed and the most cited uses past relationships between short and long rates to forecast future yields. The problem lies in the ever-changing nature of the world and these relationships.

For instance, the government debt is souring and Congress seems too dysfunctional to slow it. At the same time, the Fed is reducing its treasury holdings, while Japanese investors are finding higher competing interest rates at home. Additionally, financial regulations are limiting broker-dealer’s ability to absorb additional supply. Added all up, both supply and demand are exerting unprecedented upward pressure on bond yields.

Of course, not everyone agrees. Janet Yellen, soon after the economy registered a 4.9% annualized growth rate, argued that higher long-term yields instead simply reflected the need for the Fed to keep rates high for longer to slow the economy and, hopefully, inflation. Others have pointed out that treasuries no longer act as a hedge against the stock market, given the correlations between the two are now firmly positive. Rising bond yields (i.e., falling treasuries) have recently tended to hurt stocks. Even a potential broadening of the war in the Middle East may prove inflationary rather than an impediment to growth.

Regardless of the reason, not only is the term structure less inverted, but real rates as measured by Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities or TIPS (and discussed in my 2016 article in detail) are much higher. Whether real rates are done rising requires knowing the elusive level of R-star.

![Source: Bloomberg’s John Authers and Isabelle Lee, Points of Return[/ref]](https://alphaarchitect.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Real-Bond-Yields.jpg)

R-star

As The Financial Times correspondent Soumaya Keynes recently wrote, R-star is the equilibrium real interest rate for the economy. At this rate, investment and savings rates are in sync, and the economy hums along, not too hot or cold. Given it represents a natural resting place, economists also refer to it as the “natural rate of interest” and is notoriously difficult to estimate. When asked this summer at the Jackson Hole symposium, Federal Reserve Chairman Powell admitted that without it, “we are navigating by the stars under cloudy skies.”

That difficulty in pinning R-star down doesn’t stop economists and practitioners from trying. Economists generally agree that slower productivity growth since the 70s brought the natural rate down by reducing the incentive to invest. The 2007/08 Global Financial Crisis slowed the economy and thus investment demand even further just as savings from baby boomers and the Chinese picked up. As a result, R-star likely came down even further.

With baby boomers now retiring and spending their savings and Chinese no longer adding to their dollar reserves, the world’s saving glut has seemingly vanished. However, the demand for savings to finance our federal deficits has rarely been greater. It seems fair to conclude that even if the exact magnitude is uncertain, R-star has likely increased.

In the future, investment needs for AI and green energy could push R-star even higher. In line with this, in the last year, the Federal Reserve has increased its long-run forecast for the Federal Funds Rate by 0.8% to 3.8%.

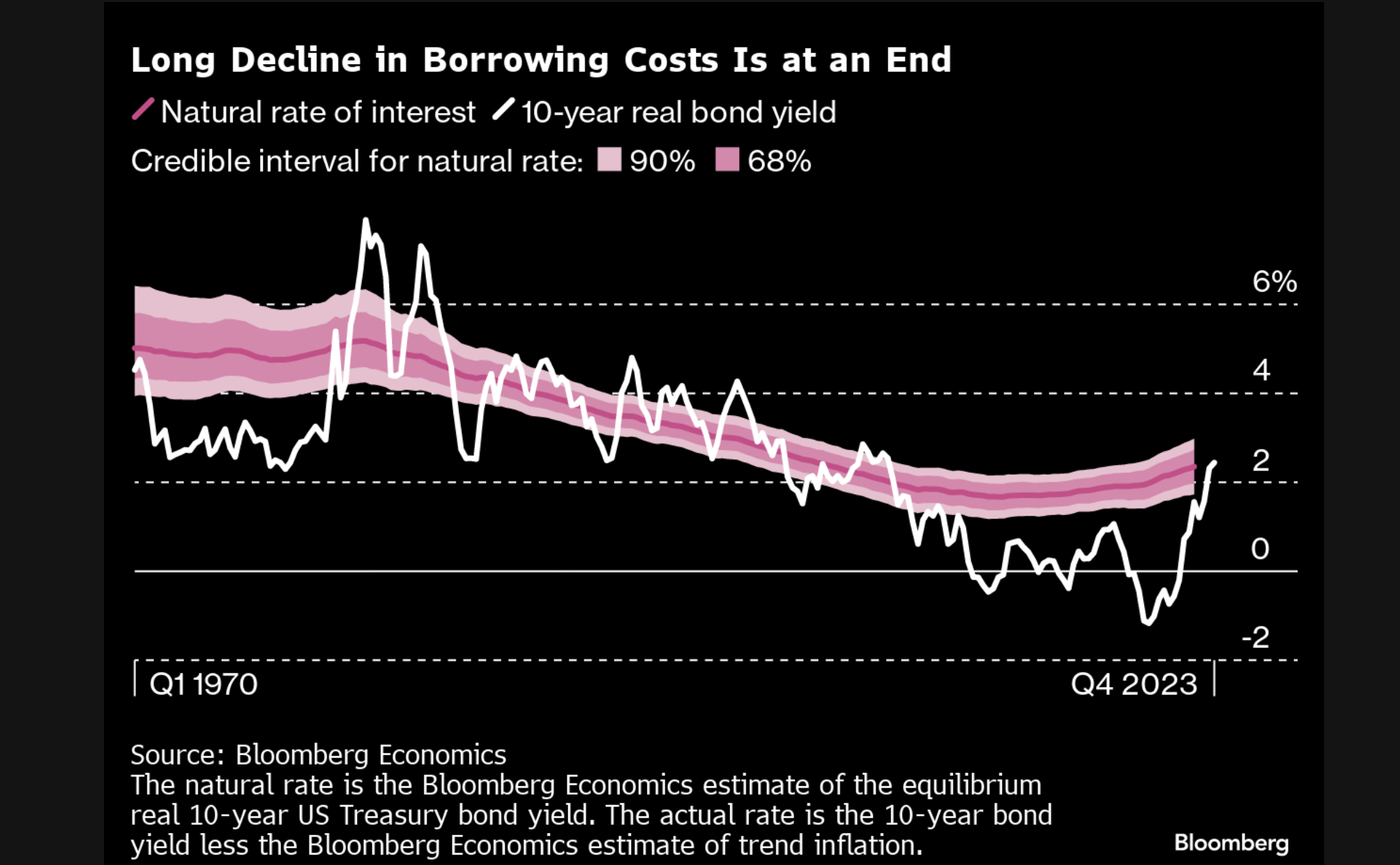

Bloomberg’s economic team is making as good an attempt as any to forecast R-star. By their measurements, the natural rate declined from roughly 5% to below 2% before a recent bounce. The actual real rate likely fluctuated around that level. The Bloomberg team forecasts that a combination of higher deficits and increased productivity and investment could boost R-star back to 4%. That level implies a 6% nominal rate!

Now What?

Fortunately, investors and their advisors don’t need to know the exact R-star rate, let alone predict where it is going. They also don’t have to calculate the correct term structure of interest rates. As the Grumpy Economist John Cochrane argued and I summarized, they should instead focus on understanding their future cash-flow needs and determining how much risk they are willing and capable of assuming to meet those needs. Real interest rates now north of 2% makes that easier. If an investor can take a moderate amount of risk, investment-grade corporate bonds and agency mortgage-backed bonds offer nominal yields as high as 6%.

Renowned credit investor Howard Marks argues that investors should consider allocating more assets to high-yield bonds yielding over 8.5% and leveraged loans offering roughly 10% yields. Of course, achieving those higher yields associated with leveraged companies requires taking on more default risk, a risk that grows in a recession when perhaps an investor’s job is at risk. Likewise, you can earn over 8% by investing in funds invested in preferred stock, stock with a set coupon but with lower payment priority relative to bonds. But these funds are both illiquid in times of stress, and because the preferred stock they hold are perpetual, they are more susceptible to higher interest rates than bonds. Understanding those risks and determining whether one can bear them may seem paramount. Still, it’s worth noting that an investor’s preferences are often not so different from those of the average investor. As such, these investors can buy the market portfolio, which reflects the average investor’s risk and reward profile.

Of course, as I’ve argued before, figuring out the market portfolio is challenging, particularly when it comes to the bond market. Popular “bond market’ funds contain neither Howard Marks’s leverage loans nor high-yield bonds. Nor do they hold TIPS and floating rate notes, which are suitable for investors on a fixed income worried about inflation going higher. These “bond market” funds do own a lot of very liquid treasuries, but higher liquidity can lower expected return, so if an investor doesn’t need the liquidity, they shouldn’t pay for it.

Conclusion

Although forecasting the future is nearly impossible for us mere mortals, we all want a clearer understanding of the factors driving up and down interest rates and where they may end up. What we need, however, is to better ensure our financial goals in the face of an unpredictable future. Higher interest rates help.

But the arduous task of determining how our projected cashflows (including from our jobs!) would withstand various shocks, including more shocks to interest rates, remains. Perhaps inflation and thus higher rates go even higher; or maybe economic growth stagnates sending interest rates lower; or some catastrophic event occurs we can’t even imagine, and we need immediate liquidity. Are we likely better prepared than average to face these uncertainties? Perhaps not, but in almost all cases, a prudent approach includes locking in rates now for at least some portion of a portfolio to better secure healthy cash-flows.

References[+]

| ↑1 | I’m using future and forward prices as interchangeable when in fact, there are slight differences given the need to post collateral daily in the futures market, but the gist is the same |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Fama, Eugene F., 1976, “Forward Rates as Predictors of Future Spot Rates,” Journal of Financial Economics 3, 361-377.

Fama, Eugene F., 1984, “The Information in the Term Structure,” Journal of Financial Economics 13, 509-576. |

About the Author: Jonathan Seed

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.